Turtles have a long and amazing fossil record, appearing around 260 million years ago, even before the earliest-known dinosaurs. By the latter most part of the age of dinosaurs, the Late Cretaceous Epoch, most of the modern turtle groups had evolved. Their fossils are extremely common in rocks that represent both freshwater and marine environments.Today's Fossil Friday is a piece of turtle shell that was collected by my colleagues and I in 2017 in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico. The shallow pits covering the surface suggest that it belongs to a trionychid - a softshell turtle, much like those that still live in North America today. This 80-million-year-old turtle was found at a diverse fossil site that also produced dinosaur bones, crocodile teeth, and large fish scales. These fossils were deposited in a freshwater environment, on a muddy floodplain near a slow-moving river.This is one of many turtle fossils discovered in the Menefee Formation by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. We will have much more to say about them in the not too distant future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Turtles have a long and amazing fossil record, appearing around 260 million years ago, even before the earliest-known dinosaurs. By the latter most part of the age of dinosaurs, the Late Cretaceous Epoch, most of the modern turtle groups had evolved. Their fossils are extremely common in rocks that represent both freshwater and marine environments.Today's Fossil Friday is a piece of turtle shell that was collected by my colleagues and I in 2017 in the Menefee Formation of New Mexico. The shallow pits covering the surface suggest that it belongs to a trionychid - a softshell turtle, much like those that still live in North America today. This 80-million-year-old turtle was found at a diverse fossil site that also produced dinosaur bones, crocodile teeth, and large fish scales. These fossils were deposited in a freshwater environment, on a muddy floodplain near a slow-moving river.This is one of many turtle fossils discovered in the Menefee Formation by the Western Science Center, Zuni Dinosaur Institute for Geosciences, and Southwest Paleontological Society. We will have much more to say about them in the not too distant future! Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - champsosaur vertebrae

Driven by a surge in volcanic activity and a devastating asteroid impact, the mass extinction 66 million years ago was one of the most cataclysmic events in Earth's long history. On land and in the sea, vast numbers of animals and plants went extinct. Among the victims were the dinosaurs, except for modern birds; the great marine reptiles; and the ammonites, coil-shelled relatives of squid and octopus. Among the survivors were the ancestors of modern birds, crocodilians, mammals, and other organisms that would shape the ecology of the planet for the next 66 million years.However, not all the animal groups that survived through the mass extinction would make it to the present day. One such animal is Champsosaurus. Champsosaurus fossils are common in the western United States and Canada, in rocks that date to just before the mass extinction and just after the extinction. Champsosaurus hung on until around 55 million years ago, when it finally went extinct.These are four Champsosaurus vertebrae from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, found by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. The two vertebrae on the left are shown in bottom view, and the two vertebrae on the right are in top view. Champsosaurus lived in freshwater and used its long toothy snout to catch fish and other prey. It could grow to around six feet long and was built a little like a small crocodile (example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History):

Driven by a surge in volcanic activity and a devastating asteroid impact, the mass extinction 66 million years ago was one of the most cataclysmic events in Earth's long history. On land and in the sea, vast numbers of animals and plants went extinct. Among the victims were the dinosaurs, except for modern birds; the great marine reptiles; and the ammonites, coil-shelled relatives of squid and octopus. Among the survivors were the ancestors of modern birds, crocodilians, mammals, and other organisms that would shape the ecology of the planet for the next 66 million years.However, not all the animal groups that survived through the mass extinction would make it to the present day. One such animal is Champsosaurus. Champsosaurus fossils are common in the western United States and Canada, in rocks that date to just before the mass extinction and just after the extinction. Champsosaurus hung on until around 55 million years ago, when it finally went extinct.These are four Champsosaurus vertebrae from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, found by the late fossil collector Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. The two vertebrae on the left are shown in bottom view, and the two vertebrae on the right are in top view. Champsosaurus lived in freshwater and used its long toothy snout to catch fish and other prey. It could grow to around six feet long and was built a little like a small crocodile (example below from the Arizona Museum of Natural History):

Fossil Friday -crocodilian teeth

Tyrannosaurs were not the only large reptilian predators prowling through North America in the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Crocodilians made rivers and lakes dangerous places to linger, even for small dinosaurs. Unlike today, with American alligators and crocodiles found only in the Southeast, during the Late Cretaceous crocodilians lived all over North America.These five teeth belong to a species of extinct crocodilian called Borealosuchus sternbergii. They were collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. At about 67 million years old, Borealosuchus shared its habitat with giant dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus,Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops. Other Fossil Friday subjects also lived alongside Borealosuchus, including the freshwater ray Myledaphus (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/fossil-friday-ray-tooth/#more-1560) and the large carnivorous lizard Palaeosaniwa (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/16/fossil-friday-lizard-vertebra/#more-1570).The skull and body of Borealosuchus resembled those of living crocodilians, suggesting that it too lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator.

Tyrannosaurs were not the only large reptilian predators prowling through North America in the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Crocodilians made rivers and lakes dangerous places to linger, even for small dinosaurs. Unlike today, with American alligators and crocodiles found only in the Southeast, during the Late Cretaceous crocodilians lived all over North America.These five teeth belong to a species of extinct crocodilian called Borealosuchus sternbergii. They were collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary Garbani. At about 67 million years old, Borealosuchus shared its habitat with giant dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus,Edmontosaurus, and Triceratops. Other Fossil Friday subjects also lived alongside Borealosuchus, including the freshwater ray Myledaphus (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/02/fossil-friday-ray-tooth/#more-1560) and the large carnivorous lizard Palaeosaniwa (https://valleyofthemastodon.wordpress.com/2018/02/16/fossil-friday-lizard-vertebra/#more-1570).The skull and body of Borealosuchus resembled those of living crocodilians, suggesting that it too lived as a semi-aquatic ambush predator.

Fossil Friday - lizard vertebra

Although the name Dinosauria means "terrible lizards", the dinosaurs are not lizards at all, but instead are their own separate group of reptiles (the "terrible" part depends on whom you ask). Even so, there were actual big lizards living alongside the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period. This is a dorsal (back) vertebra of Palaeosaniwa, a large lizard that lived at the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 67 million years ago. This vertebra, shown here from the front, was collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.Palaeosaniwa was a carnivorous lizard related to the living monitor lizards, such as the giant Komodo dragon and the goanna shown below; as such, its prey probably included small dinosaurs from time to time. Of the nearly 30 species of lizards known from North America around 67 million years ago, Palaeosaniwa is the largest, and in fact is also the biggest land-dwelling lizard from the entire Cretaceous Period. The only larger lizards around at this time were the immense mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that could reach up to 40 feet in length. Palaeosaniwa was probably around five feet long and weighed about 13 lbs, still an impressive creature even alongside titans like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops with which it shared its habitat.

Although the name Dinosauria means "terrible lizards", the dinosaurs are not lizards at all, but instead are their own separate group of reptiles (the "terrible" part depends on whom you ask). Even so, there were actual big lizards living alongside the dinosaurs during the Cretaceous Period. This is a dorsal (back) vertebra of Palaeosaniwa, a large lizard that lived at the end of the age of dinosaurs, about 67 million years ago. This vertebra, shown here from the front, was collected in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by the late Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary.Palaeosaniwa was a carnivorous lizard related to the living monitor lizards, such as the giant Komodo dragon and the goanna shown below; as such, its prey probably included small dinosaurs from time to time. Of the nearly 30 species of lizards known from North America around 67 million years ago, Palaeosaniwa is the largest, and in fact is also the biggest land-dwelling lizard from the entire Cretaceous Period. The only larger lizards around at this time were the immense mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that could reach up to 40 feet in length. Palaeosaniwa was probably around five feet long and weighed about 13 lbs, still an impressive creature even alongside titans like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops with which it shared its habitat. By Andrew McDonald

By Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - crocodile jaw

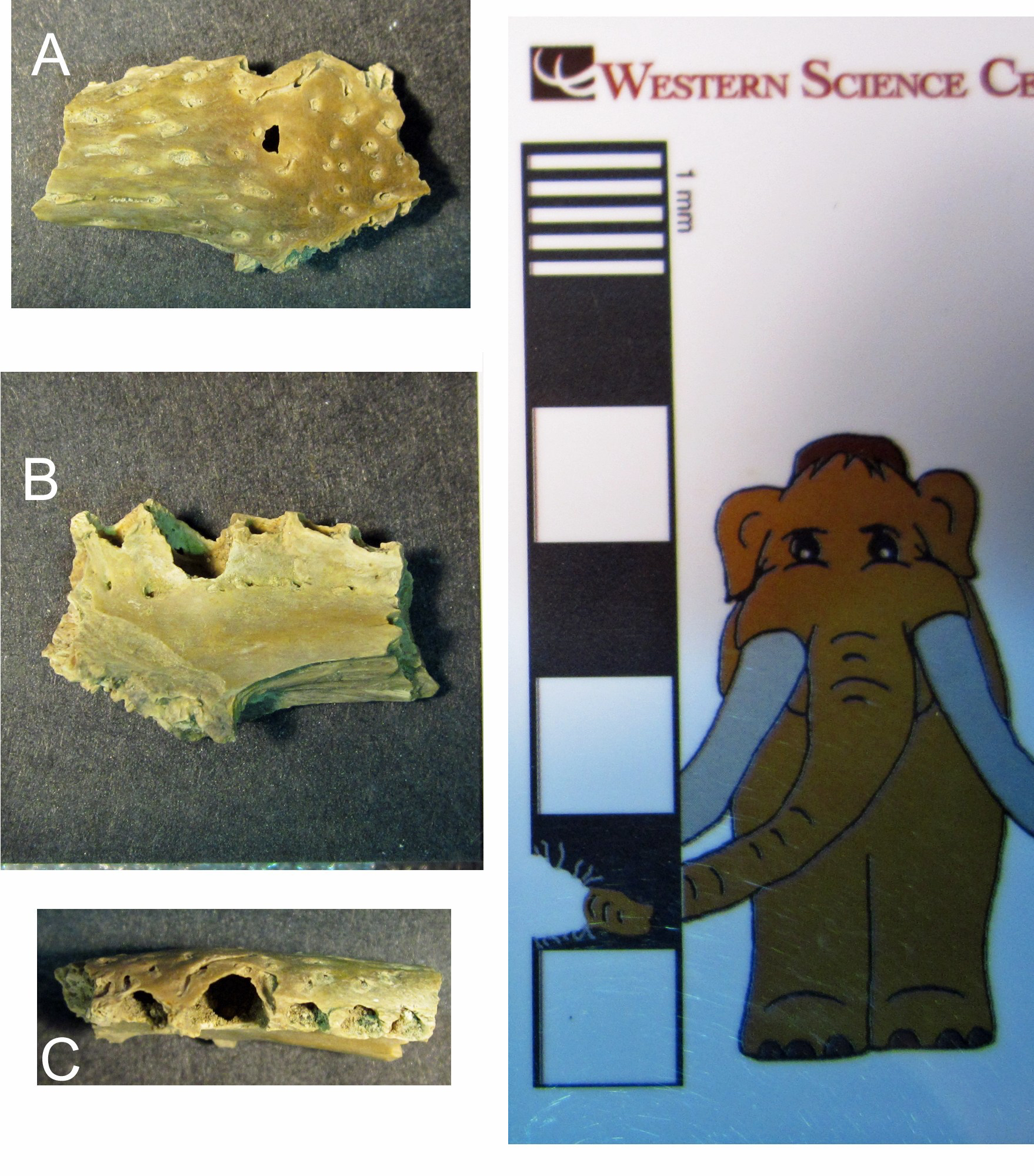

A few months ago, WSC hired Dr. Andrew McDonald as our paleontology Curator. Going forward, Andrew and I are going to split responsibility for writing Fossil Friday posts. Today is Andrew's first post. - ACDThis is part of a jaw bone of a small crocodilian, a relative of the living crocodiles and alligators. This little crocodilian lived about 67 million years ago, near the very end of the Late Cretaceous Epoch. It swam and hunted in the swamps and streams of prehistoric Montana, alongside Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and other dinosaurs near the end of their reign. This fossil was discovered in a rock layer known as the Hell Creek Formation by an accomplished local fossil collector, the late Harley Garbani, and donated to WSC by his wife Mary.This jaw bone has numerous tiny holes for the passage of blood vessels and nerves on its outer (A) and inner (B) surfaces. There are also five tooth sockets preserved (C), including three small sockets, one medium-sized socket, and one large socket, showing that the crocodilian had teeth of different sizes in its jaws when it was alive, similar to today's crocodilians.

A few months ago, WSC hired Dr. Andrew McDonald as our paleontology Curator. Going forward, Andrew and I are going to split responsibility for writing Fossil Friday posts. Today is Andrew's first post. - ACDThis is part of a jaw bone of a small crocodilian, a relative of the living crocodiles and alligators. This little crocodilian lived about 67 million years ago, near the very end of the Late Cretaceous Epoch. It swam and hunted in the swamps and streams of prehistoric Montana, alongside Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops, and other dinosaurs near the end of their reign. This fossil was discovered in a rock layer known as the Hell Creek Formation by an accomplished local fossil collector, the late Harley Garbani, and donated to WSC by his wife Mary.This jaw bone has numerous tiny holes for the passage of blood vessels and nerves on its outer (A) and inner (B) surfaces. There are also five tooth sockets preserved (C), including three small sockets, one medium-sized socket, and one large socket, showing that the crocodilian had teeth of different sizes in its jaws when it was alive, similar to today's crocodilians.

Fossil Friday - whiptail jaw fragment

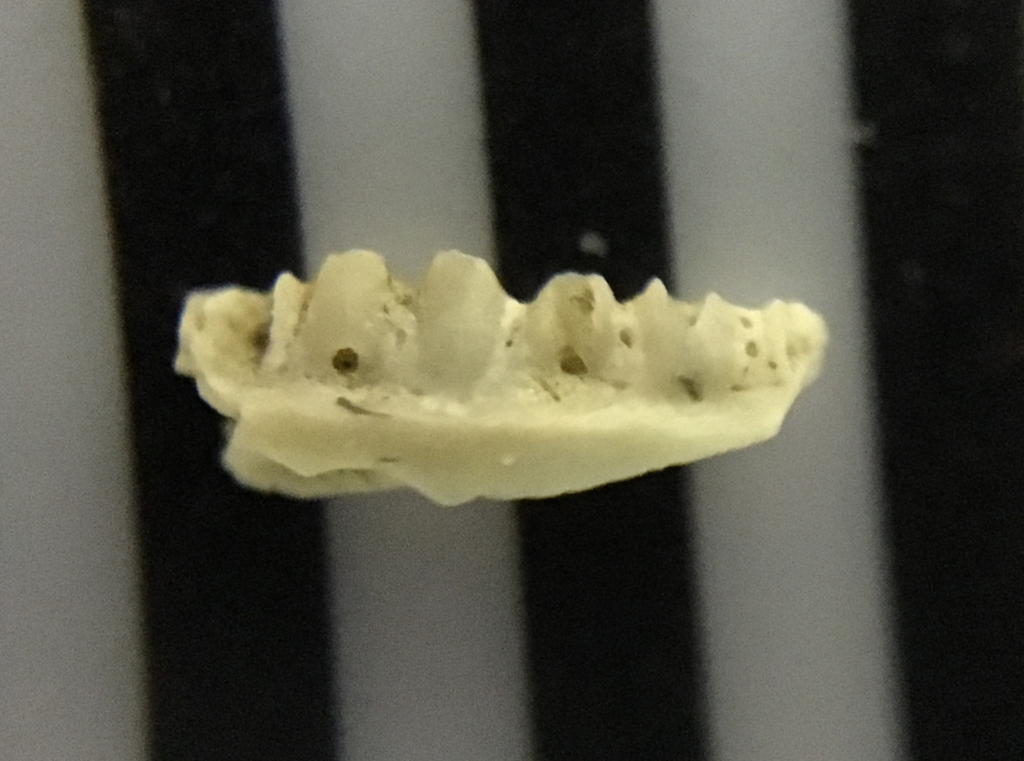

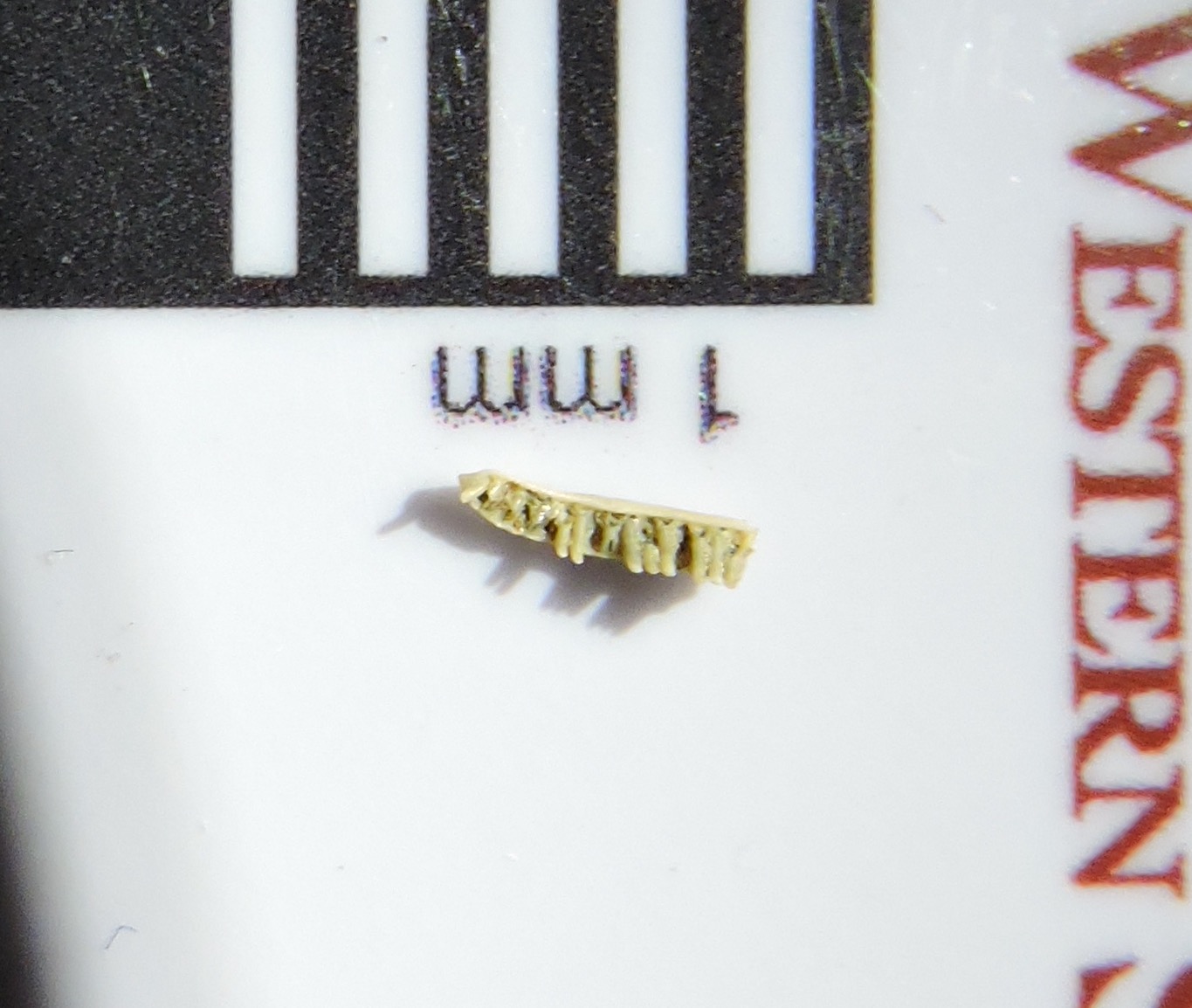

At many sites, screening sediment is among the most effective means of recovering fossils, particularly small bones. Fossils recovered through screening are actually the most common remains from Diamond Valley Lake, and are the source of most of our information about the small animal fauna.The fragment shown above is part of the dentary of a western whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis tigris (Cnemidophorous tigris in older taxonomic schemes). I'm not sure if this is the left or the right dentary, but it is the medial side, and the bases of four teeth are visible. This is a tiny fragment; the black and white bars are each 1 mm wide.Here's the lateral view:

At many sites, screening sediment is among the most effective means of recovering fossils, particularly small bones. Fossils recovered through screening are actually the most common remains from Diamond Valley Lake, and are the source of most of our information about the small animal fauna.The fragment shown above is part of the dentary of a western whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis tigris (Cnemidophorous tigris in older taxonomic schemes). I'm not sure if this is the left or the right dentary, but it is the medial side, and the bases of four teeth are visible. This is a tiny fragment; the black and white bars are each 1 mm wide.Here's the lateral view: In many lizards the dentary rises higher on the lateral side than the medial side, hiding the bases of the teeth. While four teeth are preserved, the tips of all of them are broken off. This is also apparent in occlusal view (unfortunately not with the best focus; this photo was a bit beyond the limits of my iPhone's camera):

In many lizards the dentary rises higher on the lateral side than the medial side, hiding the bases of the teeth. While four teeth are preserved, the tips of all of them are broken off. This is also apparent in occlusal view (unfortunately not with the best focus; this photo was a bit beyond the limits of my iPhone's camera): Aspidoscelis tigris is a small lizard with (as its name implies) an exceptionally long tail. The example below was at the Henry Doorly Zoo,hanging out on top of a Gila monster (Heloderma suspects):

Aspidoscelis tigris is a small lizard with (as its name implies) an exceptionally long tail. The example below was at the Henry Doorly Zoo,hanging out on top of a Gila monster (Heloderma suspects): Whiptails are common today in arid and semi-arid parts of the southwest, where they feed on insects and other arthropods such as spiders and scorpions. This specimen was recovered from the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

Whiptails are common today in arid and semi-arid parts of the southwest, where they feed on insects and other arthropods such as spiders and scorpions. This specimen was recovered from the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

Fossil Friday - horned lizard spike

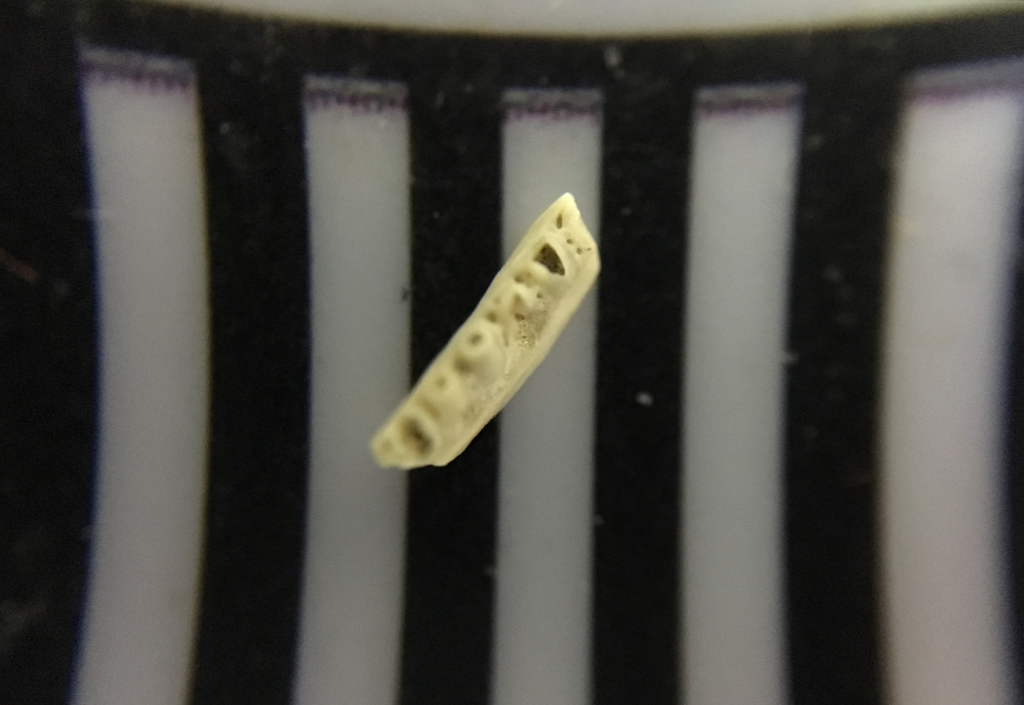

One of the things I find most intriguing about the Pleistocene is how, in spite of the impressive megafauna, it was so similar to the modern world. As I've mentioned in other posts, as with many other Pleistocene sites the fauna at Diamond Valley Lake is in many ways a lot like what we see in southern California today.The tiny fossil shown above (that's a millimeter scale) may look like a tooth at first glance. But the pitted texture is a giveaway that this is a bone, not a tooth. This is a horn from a horned lizard of the genus Phrynosoma, specifically one of the horns that projects from the parietal bone in the skull, visible below in this specimen of Phrynosoma cornutum that Brett photographed in Texas:

One of the things I find most intriguing about the Pleistocene is how, in spite of the impressive megafauna, it was so similar to the modern world. As I've mentioned in other posts, as with many other Pleistocene sites the fauna at Diamond Valley Lake is in many ways a lot like what we see in southern California today.The tiny fossil shown above (that's a millimeter scale) may look like a tooth at first glance. But the pitted texture is a giveaway that this is a bone, not a tooth. This is a horn from a horned lizard of the genus Phrynosoma, specifically one of the horns that projects from the parietal bone in the skull, visible below in this specimen of Phrynosoma cornutum that Brett photographed in Texas: There are a number of different species of horned lizards that are each endemic to different parts of North America, and one of the ways they differ is in the size and shape of their horns. Compare the horns on the Texas lizard above to those on Phyrnosoma douglasii from South Dakota:

There are a number of different species of horned lizards that are each endemic to different parts of North America, and one of the ways they differ is in the size and shape of their horns. Compare the horns on the Texas lizard above to those on Phyrnosoma douglasii from South Dakota: The southern California horned lizard species is Phrynosoma coronatum, which I've never had the opportunity to photograph in the wild. Its skull, however, is somewhat similar to the Texas species with large parietal horns, as can be seen in this comparison image.Horned lizards live in relatively arid areas, which seems to be a common theme with the small Pleistocene animals found at Diamond Valley Lake. They are specialist predators of ants, especially harvester ants, so the presence of Phyrnosoma at Diamond Valley Lake implies the presence of ants there as well, even though they have not been found as fossils in those deposits.

The southern California horned lizard species is Phrynosoma coronatum, which I've never had the opportunity to photograph in the wild. Its skull, however, is somewhat similar to the Texas species with large parietal horns, as can be seen in this comparison image.Horned lizards live in relatively arid areas, which seems to be a common theme with the small Pleistocene animals found at Diamond Valley Lake. They are specialist predators of ants, especially harvester ants, so the presence of Phyrnosoma at Diamond Valley Lake implies the presence of ants there as well, even though they have not been found as fossils in those deposits.

Fossil Friday - fence lizard jaw

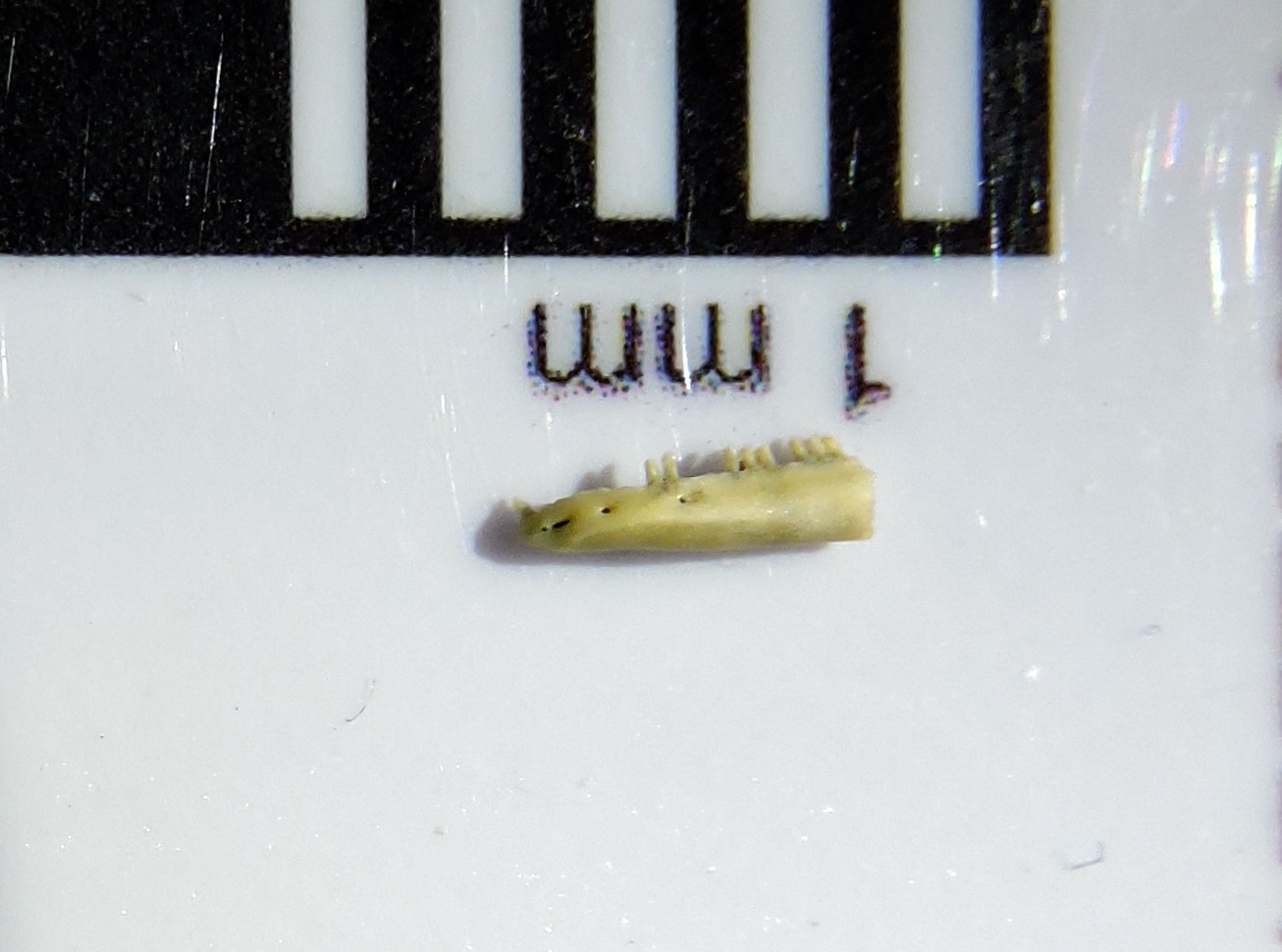

Lizards are a common site today across southern California, and that was true in the Pleistocene as well. Large numbers of lizard bones were recovered from Diamond Valley Lake sediments, including the one shown here.This is a partial left lower jaw from a lizard of the genus Sceloporus, most likely a western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentals). These small lizards live all over California today, and are often sunning in my driveway when I get home from work:

Lizards are a common site today across southern California, and that was true in the Pleistocene as well. Large numbers of lizard bones were recovered from Diamond Valley Lake sediments, including the one shown here.This is a partial left lower jaw from a lizard of the genus Sceloporus, most likely a western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentals). These small lizards live all over California today, and are often sunning in my driveway when I get home from work: As I mentioned in an earlier post, mammals have lower jaws that consist of a single bone, the dentary, on each side. In other vertebrates the dentary is one of several bones that make up the lower jaw. This particular specimen includes the anterior part of the left dentary, while the back part of the dentary and the other lower jaw bones are all missing. The view at the top is a lateral (side) view, with anterior to the left. Below is a medial view, anterior to the right:

As I mentioned in an earlier post, mammals have lower jaws that consist of a single bone, the dentary, on each side. In other vertebrates the dentary is one of several bones that make up the lower jaw. This particular specimen includes the anterior part of the left dentary, while the back part of the dentary and the other lower jaw bones are all missing. The view at the top is a lateral (side) view, with anterior to the left. Below is a medial view, anterior to the right: In this view we can more clearly see there are nine complete teeth preserved, and the bases of at least five others.Here's a dorsal or occlusal view, anterior to the left:

In this view we can more clearly see there are nine complete teeth preserved, and the bases of at least five others.Here's a dorsal or occlusal view, anterior to the left: Fence lizards are widespread today and live in a variety of environments, so the presence of fence lizards doesn't really give us any information about the paleoenvironmental conditions at Diamond Valley Lake during the Pleistocene. But if you traveled back to the Pleistocene and could pull your eyes away from the mammoths, mastodons, and other megafauna long enough to look at the small animals among the shrubs and rocks, what you would see would look a lot like modern-day California.

Fence lizards are widespread today and live in a variety of environments, so the presence of fence lizards doesn't really give us any information about the paleoenvironmental conditions at Diamond Valley Lake during the Pleistocene. But if you traveled back to the Pleistocene and could pull your eyes away from the mammoths, mastodons, and other megafauna long enough to look at the small animals among the shrubs and rocks, what you would see would look a lot like modern-day California.

Fossil Friday - collared lizard vertebra

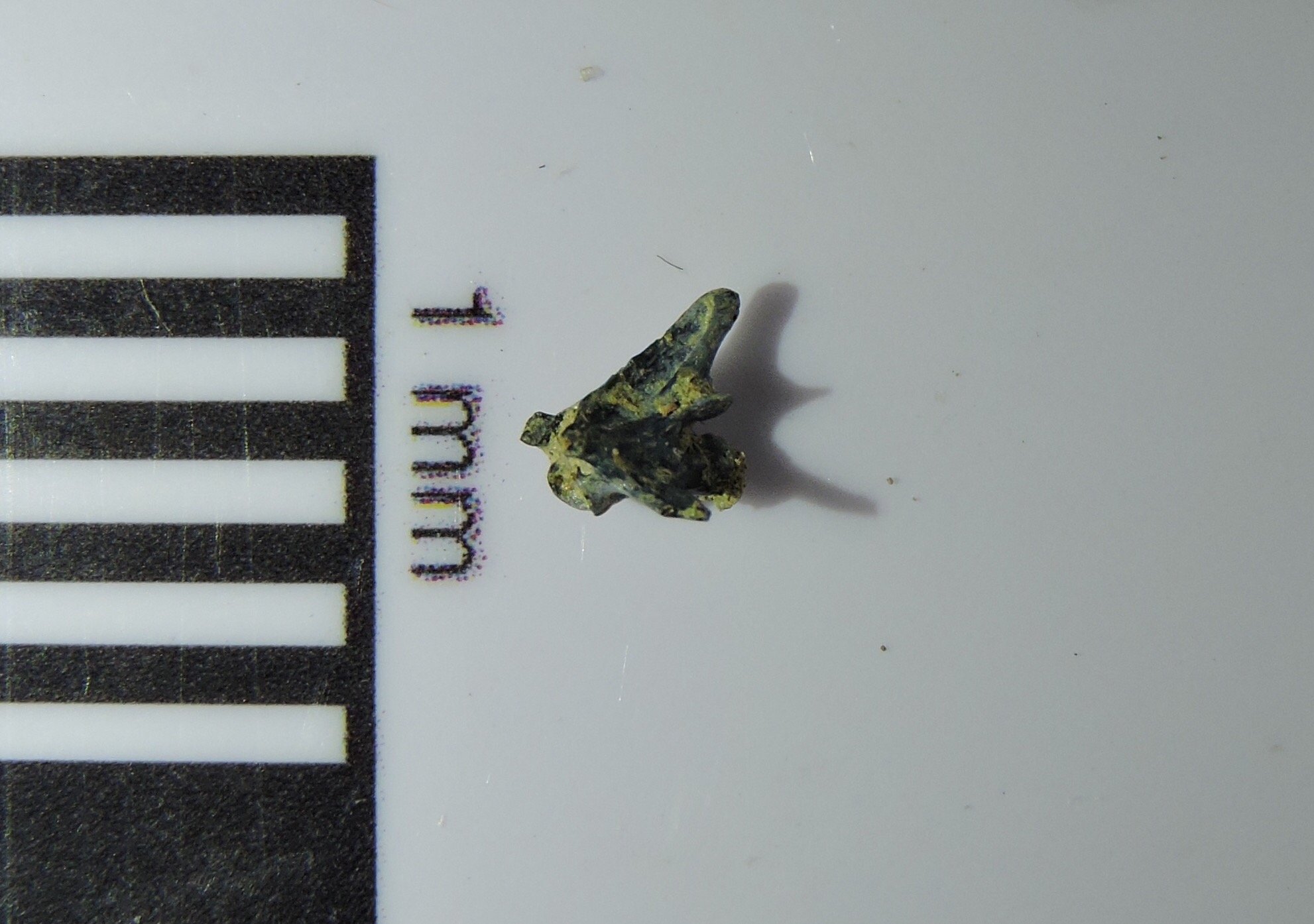

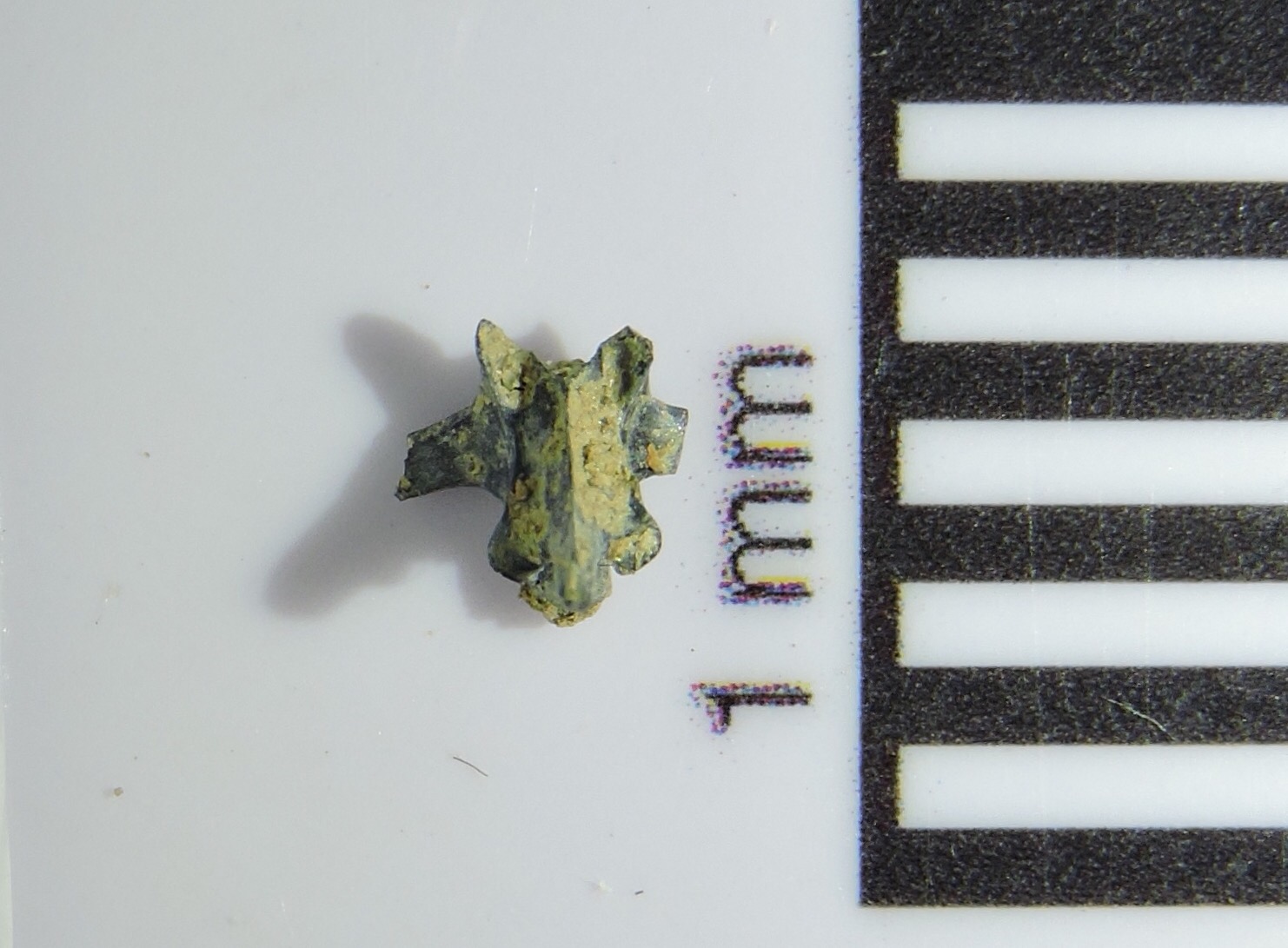

From a geological standpoint the Ice Age was not very long ago. Almost all the plant and animal species around today are survivors of the extinction that took place at the end of the Pleistocene. In many Ice Age deposits, while extinct megafauna get the most attention, the most widespread fossils are from species that are still with us today.Above is a caudal (tail) vertebra from a collared lizard of the genus Crotaphytus. It's shown in left lateral view, with the front of the bone to the left. Below is a dorsal view of the same bone, with anterior toward the top:

From a geological standpoint the Ice Age was not very long ago. Almost all the plant and animal species around today are survivors of the extinction that took place at the end of the Pleistocene. In many Ice Age deposits, while extinct megafauna get the most attention, the most widespread fossils are from species that are still with us today.Above is a caudal (tail) vertebra from a collared lizard of the genus Crotaphytus. It's shown in left lateral view, with the front of the bone to the left. Below is a dorsal view of the same bone, with anterior toward the top: In this view we can see that the transverse processes that stick off each side of the vertebra are broken, as is the right prezygopophysis (the prezygopophyses are the bony spurs projecting off the front of the vertebra; they would articulate with the vertebra immediately ahead of this one). Besides this slight damage, the black color suggests this bone has been burned in a fire, as is the case with a number of other bones from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits.Collared lizards are widespread in Mexico and the southern United States west of the Mississippi River, especially in more arid environments. They are fast-moving carnivorous lizards that feed on insects and small mammals. There are several living species, some of which include brightly-colored males with banding around their necks that inspired their common name. Unfortunately, we probably can't identify the species of collared lizard based solely on an isolated tail vertebra, but we can say that these colorful lizards were present in the region just as they are today.

In this view we can see that the transverse processes that stick off each side of the vertebra are broken, as is the right prezygopophysis (the prezygopophyses are the bony spurs projecting off the front of the vertebra; they would articulate with the vertebra immediately ahead of this one). Besides this slight damage, the black color suggests this bone has been burned in a fire, as is the case with a number of other bones from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits.Collared lizards are widespread in Mexico and the southern United States west of the Mississippi River, especially in more arid environments. They are fast-moving carnivorous lizards that feed on insects and small mammals. There are several living species, some of which include brightly-colored males with banding around their necks that inspired their common name. Unfortunately, we probably can't identify the species of collared lizard based solely on an isolated tail vertebra, but we can say that these colorful lizards were present in the region just as they are today.

Fossil Friday - colubrids snake vertebra

In recognition of World Snake Day (which was yesterday), for today's Fossil Friday we have a Pleistocene snake from Diamond Valley Lake.Reptiles are common in Southern California today, and the same was true during the Pleistocene, including turtles, lizards, and snakes. While rattlesnakes may get more attention, the most diverse and widespread group of snakes are the family Colubridae; in fact, more than half of the extant snake species are colubrids. With such a common group, it's not surprising that their vertebrae turn up fairly commonly as fossils.At the top of the page is a dorsal vertebra, from the region that makes up the bulk of a snake's body. The vertebra itself is about 3 millimeters across at the widest point, but in the living snake a rib would have been attached to each side. It's shown here in close to anterior view, but slightly below and to the right. Like other snakes this vertebra is procoelous, meaning that it articulates with other vertebrae in part through ball-and-socket joints. The socket on the front of the vertebra is visible here; there's a corresponding ball joint on the other end of the vertebra.Colubrids are still diverse in Southern California, and include such diverse forms as king snakes, garter snakes, and gopher snakes (such as Pituophis catanifer, below, photographed on the museum campus). With such a range of closely-related species to choose from, so far we can only say that this vertebra represents some type of colubrid.

In recognition of World Snake Day (which was yesterday), for today's Fossil Friday we have a Pleistocene snake from Diamond Valley Lake.Reptiles are common in Southern California today, and the same was true during the Pleistocene, including turtles, lizards, and snakes. While rattlesnakes may get more attention, the most diverse and widespread group of snakes are the family Colubridae; in fact, more than half of the extant snake species are colubrids. With such a common group, it's not surprising that their vertebrae turn up fairly commonly as fossils.At the top of the page is a dorsal vertebra, from the region that makes up the bulk of a snake's body. The vertebra itself is about 3 millimeters across at the widest point, but in the living snake a rib would have been attached to each side. It's shown here in close to anterior view, but slightly below and to the right. Like other snakes this vertebra is procoelous, meaning that it articulates with other vertebrae in part through ball-and-socket joints. The socket on the front of the vertebra is visible here; there's a corresponding ball joint on the other end of the vertebra.Colubrids are still diverse in Southern California, and include such diverse forms as king snakes, garter snakes, and gopher snakes (such as Pituophis catanifer, below, photographed on the museum campus). With such a range of closely-related species to choose from, so far we can only say that this vertebra represents some type of colubrid.

Fossil Friday - western pond turtle costal plate

Fossil preservation is a tricky thing, and the variables involved in fossilization can have a major effect on what eventually gets preserved (a major subfield of paleontology, taphonomy, looks at this very issue). For vertebrates, one factor that can give you a high preservation potential is having a lot of bones, so that a large percentage of your body mass is more likely to survive. With their extensive bony shells, turtles should be a prime candidate for fossilization, and sure enough, large numbers were found in the Pleistocene Diamond Valley Lake fauna. Of course, having lots of bones is no guarantee that they'll survive in one piece; most of our turtle remains are fragments of the shell, and we have nothing even remotely approaching a complete turtle skeleton.Turtle shells have two main pieces, the carapace on the turtle's dorsal side and the plastron on the ventral side. The carapace and plastron, in turn, are each made up of numerous smaller bones. The piece shown above is from the carapace, technically called the first right costal, which formed the front right part of the shell. It's shown here in dorsal view; if the skeleton were complete, the turtle's skull would have been out of the image at the upper left. Here's a ventral view of the same bone (since this is from the carapace, it's like you're inside the turtle looking out):

Fossil preservation is a tricky thing, and the variables involved in fossilization can have a major effect on what eventually gets preserved (a major subfield of paleontology, taphonomy, looks at this very issue). For vertebrates, one factor that can give you a high preservation potential is having a lot of bones, so that a large percentage of your body mass is more likely to survive. With their extensive bony shells, turtles should be a prime candidate for fossilization, and sure enough, large numbers were found in the Pleistocene Diamond Valley Lake fauna. Of course, having lots of bones is no guarantee that they'll survive in one piece; most of our turtle remains are fragments of the shell, and we have nothing even remotely approaching a complete turtle skeleton.Turtle shells have two main pieces, the carapace on the turtle's dorsal side and the plastron on the ventral side. The carapace and plastron, in turn, are each made up of numerous smaller bones. The piece shown above is from the carapace, technically called the first right costal, which formed the front right part of the shell. It's shown here in dorsal view; if the skeleton were complete, the turtle's skull would have been out of the image at the upper left. Here's a ventral view of the same bone (since this is from the carapace, it's like you're inside the turtle looking out): Most vertebrates that have bony armor (armadillos or crocodiles, for example) make their armor from dermal bones. These are bones that are embedded in the skin and generally have no direct connection to the rest of the skeleton. Many of the bones in a turtle's carapace are different in that they are attached directly to internal bones. The costal plates are attached to the ribs; this is more obvious in an oblique view of the ventral side of the bone, where the rib is clearly visible:

Most vertebrates that have bony armor (armadillos or crocodiles, for example) make their armor from dermal bones. These are bones that are embedded in the skin and generally have no direct connection to the rest of the skeleton. Many of the bones in a turtle's carapace are different in that they are attached directly to internal bones. The costal plates are attached to the ribs; this is more obvious in an oblique view of the ventral side of the bone, where the rib is clearly visible: This particular costal bone is from a western pond turtle, Actinemys marmorota. These turtles are still found on the west coast, yet somehow I've never photographed one, even though I have dozens of turtle photos including every other genus in the family Emydidae. The closest relatives I've photographed are Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) from the upper Midwest:

This particular costal bone is from a western pond turtle, Actinemys marmorota. These turtles are still found on the west coast, yet somehow I've never photographed one, even though I have dozens of turtle photos including every other genus in the family Emydidae. The closest relatives I've photographed are Blanding's turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) from the upper Midwest: ...and the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) from the east coast:

...and the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) from the east coast: These three species are all closely related, and are in the same subfamily. In fact, until a few years ago Actinemys marmorota was placed in the genus Clemmys (our labels at WSC actually list these specimens as Clemmys marmorota); some workers have also proposed that Actimemys and Emydoidea in the same genus, Emys.

These three species are all closely related, and are in the same subfamily. In fact, until a few years ago Actinemys marmorota was placed in the genus Clemmys (our labels at WSC actually list these specimens as Clemmys marmorota); some workers have also proposed that Actimemys and Emydoidea in the same genus, Emys.

Fossil Friday - iguanid humerus

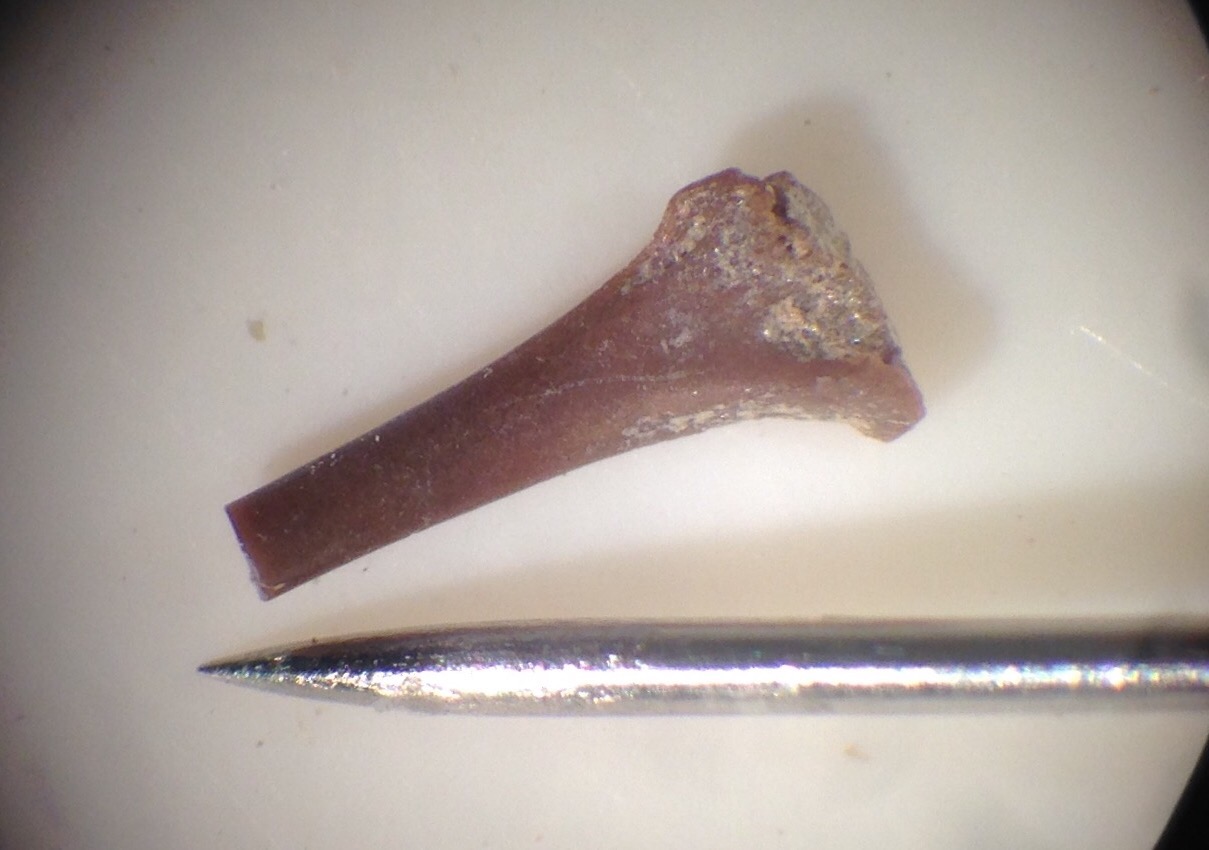

In terms of numbers, most of the Pleistocene fossils from Diamond Valley Lake are from small animals, especially rodents and other small mammals. But there are non-mammals represented as well, such as the rattlesnake I posted a few weeks ago, and today's example, a lizard.This specimen is the proximal part of the left humerus, the upper arm bone. It has been identified as coming from the Family Iguanidae. The most famous iguanid is Iguana itself, but the family is fairly diverse with a number of different genera. Two species still live in Southern California, the desert iguana Dipsosaurus dorsalis:

In terms of numbers, most of the Pleistocene fossils from Diamond Valley Lake are from small animals, especially rodents and other small mammals. But there are non-mammals represented as well, such as the rattlesnake I posted a few weeks ago, and today's example, a lizard.This specimen is the proximal part of the left humerus, the upper arm bone. It has been identified as coming from the Family Iguanidae. The most famous iguanid is Iguana itself, but the family is fairly diverse with a number of different genera. Two species still live in Southern California, the desert iguana Dipsosaurus dorsalis: ... and the common chuckwalla Sauromalus ater:

... and the common chuckwalla Sauromalus ater: There is also an extinct iguana from Riverside County, Pumila novaceki, that has been found in somewhat older sediments than those found at Diamond Valley Lake. This humerus could have come from any of these small iguanids.

There is also an extinct iguana from Riverside County, Pumila novaceki, that has been found in somewhat older sediments than those found at Diamond Valley Lake. This humerus could have come from any of these small iguanids.

Fossil Friday - rattlesnake vertebra

It's springtime, and in the Inland Empire that means snakes! The Pleistocene fossils from Southern California make it clear that this has been the case for a long time, as demonstrated by the vertebra shown above.This partial vertebra is probably from the genus Crotalus, a rattlesnake, shownfrom the front (anterior view). Snake vertebrae are procoelous, meaning that the vertebrae articulate with each other with a ball-and-socket joint with the socket on the front of the vertebra; the socket is clearly visible in the image above.Snakes have a lot of vertebrae, up to several hundred in some species, so each individual vertebra is typically not very big. This vertebra is a little over a centimeter across, which represents a pretty large rattlesnake.

It's springtime, and in the Inland Empire that means snakes! The Pleistocene fossils from Southern California make it clear that this has been the case for a long time, as demonstrated by the vertebra shown above.This partial vertebra is probably from the genus Crotalus, a rattlesnake, shownfrom the front (anterior view). Snake vertebrae are procoelous, meaning that the vertebrae articulate with each other with a ball-and-socket joint with the socket on the front of the vertebra; the socket is clearly visible in the image above.Snakes have a lot of vertebrae, up to several hundred in some species, so each individual vertebra is typically not very big. This vertebra is a little over a centimeter across, which represents a pretty large rattlesnake.