After the turmoil of end-of-year administrative duties, I'm now starting to turn my attention back to the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project.The subject of these week's Fossil Friday is a skull fragment that is being added to our dataset.The fragment is shown above in lateral view, with an annotated version below:

After the turmoil of end-of-year administrative duties, I'm now starting to turn my attention back to the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project.The subject of these week's Fossil Friday is a skull fragment that is being added to our dataset.The fragment is shown above in lateral view, with an annotated version below: While most of the skull is missing, there is a substantial part of the left front preserved, including the socket for the left tusk, the upper left 2nd molar, and part of the bottom edge of the eye socket. Below is a partial ventral view (part of this side is hidden by the plaster jacket:

While most of the skull is missing, there is a substantial part of the left front preserved, including the socket for the left tusk, the upper left 2nd molar, and part of the bottom edge of the eye socket. Below is a partial ventral view (part of this side is hidden by the plaster jacket: In this view it's clear that the 2nd molar is mostly intact. It's also quite heavily worn; this was a mature mastodon, probably almost as old as Max. It's 3rd molar should have been partially erupted, but that part of the skull is not preserved. The 2nd molar is 121 mm long, which is actually the longest M2 I've measured in a California specimen by a fairly large margin. But it's also only a little over 75 mm wide, making it unusually narrow even for a California specimen. The socket for the tusk is partially crushed, so I'm not confident about measurements of its diameter, but it seems on the small side; it's possible this is a female specimen.

In this view it's clear that the 2nd molar is mostly intact. It's also quite heavily worn; this was a mature mastodon, probably almost as old as Max. It's 3rd molar should have been partially erupted, but that part of the skull is not preserved. The 2nd molar is 121 mm long, which is actually the longest M2 I've measured in a California specimen by a fairly large margin. But it's also only a little over 75 mm wide, making it unusually narrow even for a California specimen. The socket for the tusk is partially crushed, so I'm not confident about measurements of its diameter, but it seems on the small side; it's possible this is a female specimen.

Fossil Friday - Megalonyx tooth

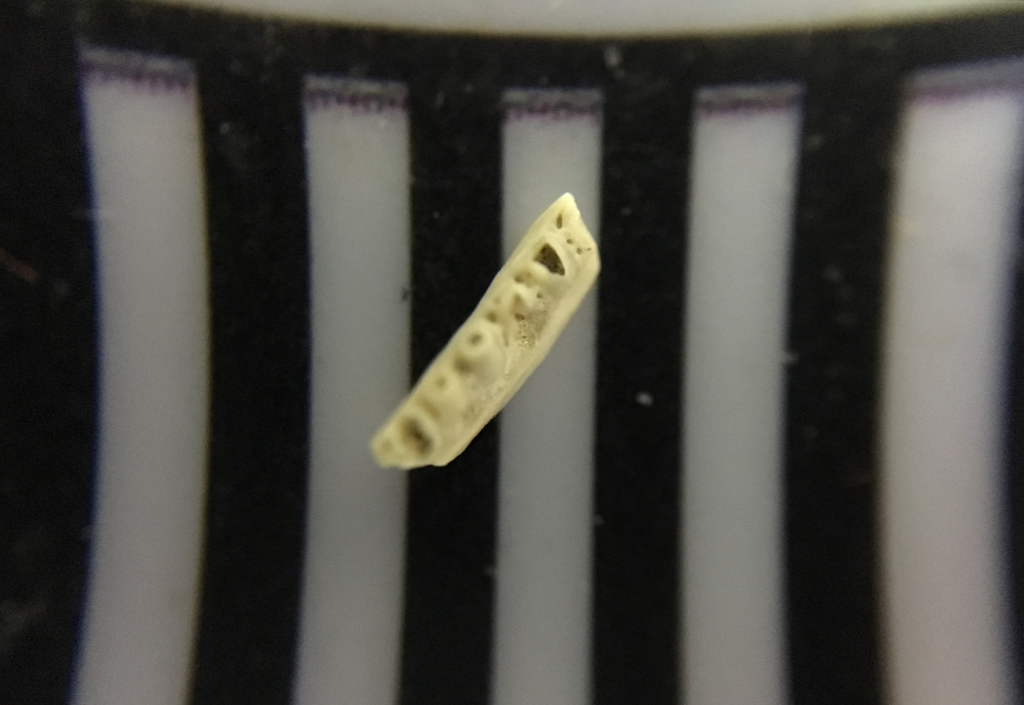

On January 17, Western Science Center is kicking off a new monthly lecture series. Our first speaker will be H. Greg McDonald from the Bureau of Land Management, who is going to be talking about ground sloths, animals which make up a substantial part of the Diamond Valley Lake fauna.One of the the more rare sloths from Diamond Valley Lake is Megalonyx jeffersonii, which is known from fewer than a dozen bones including the isolated tooth shown above. Sloth teeth are unusual compared to most other mammals. The teeth have no enamel, and instead are composed of different layers of dentine and cementum. There are no deciduous teeth, and the teeth that are present grow continuously through the sloth's life. With no deciduous teeth, no enamel, and very little variation between different tooth position (with the exception of the first tooth and the last tooth in some species), it's actually very difficult to tell which teeth are actually represented in the sloth's jaw.The Megalonyx tooth shown above is a cheek tooth, with the occlusal surface of the tooth at the top. When the tooth first starts growing, it is a simple peg at the the occlusal end. The sculptured surface is entirely the result of wear from food and from occlusion with the opposing tooth, so the usual methods of tracing tooth evolution by examining variation in the occlusal surfaces don't work with sloths.If you're in the area, I encourage you to come by the museum on January 17 for Dr. McDonald's lecture to learn more about sloths.

On January 17, Western Science Center is kicking off a new monthly lecture series. Our first speaker will be H. Greg McDonald from the Bureau of Land Management, who is going to be talking about ground sloths, animals which make up a substantial part of the Diamond Valley Lake fauna.One of the the more rare sloths from Diamond Valley Lake is Megalonyx jeffersonii, which is known from fewer than a dozen bones including the isolated tooth shown above. Sloth teeth are unusual compared to most other mammals. The teeth have no enamel, and instead are composed of different layers of dentine and cementum. There are no deciduous teeth, and the teeth that are present grow continuously through the sloth's life. With no deciduous teeth, no enamel, and very little variation between different tooth position (with the exception of the first tooth and the last tooth in some species), it's actually very difficult to tell which teeth are actually represented in the sloth's jaw.The Megalonyx tooth shown above is a cheek tooth, with the occlusal surface of the tooth at the top. When the tooth first starts growing, it is a simple peg at the the occlusal end. The sculptured surface is entirely the result of wear from food and from occlusion with the opposing tooth, so the usual methods of tracing tooth evolution by examining variation in the occlusal surfaces don't work with sloths.If you're in the area, I encourage you to come by the museum on January 17 for Dr. McDonald's lecture to learn more about sloths.

Fossil Friday - bat jaw

Earlier this week we had our staff holiday party at the Western Science Center, where we watched The Nightmare Before Christmas. That inspired this week's Fossil Friday topic.Above is the partial right dentary (lower jaw) of a western pipistrelle bat, Parastrellus hesperus. It's shown in lateral view, with anterior to the left, and the black and white bars under it are each 1 mm wide; this is a tiny jaw! The single preserved tooth is the lower third molar. Below is medial view:

Earlier this week we had our staff holiday party at the Western Science Center, where we watched The Nightmare Before Christmas. That inspired this week's Fossil Friday topic.Above is the partial right dentary (lower jaw) of a western pipistrelle bat, Parastrellus hesperus. It's shown in lateral view, with anterior to the left, and the black and white bars under it are each 1 mm wide; this is a tiny jaw! The single preserved tooth is the lower third molar. Below is medial view: Pipistrelles are not a common component of the Diamond Valley Lake fauna, but their presence is not surprising. They are currently common throughout the southwest, especially in desert areas; we occasionally find them roosting on the museum buildings. While widespread, they are not particularly gregarious, and are usually found alone roosting in rock crevices during the day. Like many other bats, they are voracious predators of insects.Pipistrelles are one of the numerous small animal species present in the DVL fauna that are still common in southern California today. They form an interesting contrast with the large animal fauna, which is almost completely different from what currently lives here.

Pipistrelles are not a common component of the Diamond Valley Lake fauna, but their presence is not surprising. They are currently common throughout the southwest, especially in desert areas; we occasionally find them roosting on the museum buildings. While widespread, they are not particularly gregarious, and are usually found alone roosting in rock crevices during the day. Like many other bats, they are voracious predators of insects.Pipistrelles are one of the numerous small animal species present in the DVL fauna that are still common in southern California today. They form an interesting contrast with the large animal fauna, which is almost completely different from what currently lives here.

Fossil Friday - horse skull

Among the large animals recovered during the Diamond Valley Lake excavation, fully 1/5 of the specimens came from horses; only bison bones were more common among the large animals. There are two species of horse represented at DVL. The smaller species, Equus conversidens, is exceptionally rare in the deposit, and nearly all the recovered specimens belong to the larger Equus occidentalis. Reflecting this, there are a number of E. occidentalis skulls in the WSC collections.The specimen shown above is a partial skull of E. occidentalis seen in ventral view, with anterior to the right. The incisors are missing, but otherwise the right dentition is almost complete. The right teeth are labeled below:

Among the large animals recovered during the Diamond Valley Lake excavation, fully 1/5 of the specimens came from horses; only bison bones were more common among the large animals. There are two species of horse represented at DVL. The smaller species, Equus conversidens, is exceptionally rare in the deposit, and nearly all the recovered specimens belong to the larger Equus occidentalis. Reflecting this, there are a number of E. occidentalis skulls in the WSC collections.The specimen shown above is a partial skull of E. occidentalis seen in ventral view, with anterior to the right. The incisors are missing, but otherwise the right dentition is almost complete. The right teeth are labeled below: The only bones visible in this view are the maxillae, which hold the teeth, and a small part of the palatines, which form the curve at the posterior end of the palate (on the left in this image). That curve also forms the front edge of the interior nares, where the nostrils pass through the skull.This individual was an adult horse, with all of its permanent teeth erupted and showing wear. It was recovered from the West Dam area, which includes the most recent Pleistocene deposits in DVL. Carbon dates on samples from the West Dam area were all less than 20,000 years old, and most were less than 14,000 years (Springer et al. 2009).Reference:Springer, K., E. Scott, J. C. Sagebiel, and L. K. Murray, 2009. The Diamond Valley Lake Local Fauna: Late Pleistocene vertebrates from inland Southern California. In L. B. Albright III (ed.), Papers on Geology, Vertebrate Paleontology, and Biostratigraphy in Honor of Michael O. Woodburne. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 65:217-235.

The only bones visible in this view are the maxillae, which hold the teeth, and a small part of the palatines, which form the curve at the posterior end of the palate (on the left in this image). That curve also forms the front edge of the interior nares, where the nostrils pass through the skull.This individual was an adult horse, with all of its permanent teeth erupted and showing wear. It was recovered from the West Dam area, which includes the most recent Pleistocene deposits in DVL. Carbon dates on samples from the West Dam area were all less than 20,000 years old, and most were less than 14,000 years (Springer et al. 2009).Reference:Springer, K., E. Scott, J. C. Sagebiel, and L. K. Murray, 2009. The Diamond Valley Lake Local Fauna: Late Pleistocene vertebrates from inland Southern California. In L. B. Albright III (ed.), Papers on Geology, Vertebrate Paleontology, and Biostratigraphy in Honor of Michael O. Woodburne. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin 65:217-235.

Fossil Friday - whiptail jaw fragment

At many sites, screening sediment is among the most effective means of recovering fossils, particularly small bones. Fossils recovered through screening are actually the most common remains from Diamond Valley Lake, and are the source of most of our information about the small animal fauna.The fragment shown above is part of the dentary of a western whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis tigris (Cnemidophorous tigris in older taxonomic schemes). I'm not sure if this is the left or the right dentary, but it is the medial side, and the bases of four teeth are visible. This is a tiny fragment; the black and white bars are each 1 mm wide.Here's the lateral view:

At many sites, screening sediment is among the most effective means of recovering fossils, particularly small bones. Fossils recovered through screening are actually the most common remains from Diamond Valley Lake, and are the source of most of our information about the small animal fauna.The fragment shown above is part of the dentary of a western whiptail lizard, Aspidoscelis tigris (Cnemidophorous tigris in older taxonomic schemes). I'm not sure if this is the left or the right dentary, but it is the medial side, and the bases of four teeth are visible. This is a tiny fragment; the black and white bars are each 1 mm wide.Here's the lateral view: In many lizards the dentary rises higher on the lateral side than the medial side, hiding the bases of the teeth. While four teeth are preserved, the tips of all of them are broken off. This is also apparent in occlusal view (unfortunately not with the best focus; this photo was a bit beyond the limits of my iPhone's camera):

In many lizards the dentary rises higher on the lateral side than the medial side, hiding the bases of the teeth. While four teeth are preserved, the tips of all of them are broken off. This is also apparent in occlusal view (unfortunately not with the best focus; this photo was a bit beyond the limits of my iPhone's camera): Aspidoscelis tigris is a small lizard with (as its name implies) an exceptionally long tail. The example below was at the Henry Doorly Zoo,hanging out on top of a Gila monster (Heloderma suspects):

Aspidoscelis tigris is a small lizard with (as its name implies) an exceptionally long tail. The example below was at the Henry Doorly Zoo,hanging out on top of a Gila monster (Heloderma suspects): Whiptails are common today in arid and semi-arid parts of the southwest, where they feed on insects and other arthropods such as spiders and scorpions. This specimen was recovered from the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

Whiptails are common today in arid and semi-arid parts of the southwest, where they feed on insects and other arthropods such as spiders and scorpions. This specimen was recovered from the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

Fossil Friday - coyote jaw

The deer bones I talked about a few weeks ago are part of a small assemblage from a housing development in Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. Among the other remains in the collection was a partial dentary (lower jaw) from a carnivore.The fragment is a right dentary, shown above in lateral view with anterior to the right. Below is medial view, with anterior to the left:

The deer bones I talked about a few weeks ago are part of a small assemblage from a housing development in Murrieta, in southwestern Riverside County. Among the other remains in the collection was a partial dentary (lower jaw) from a carnivore.The fragment is a right dentary, shown above in lateral view with anterior to the right. Below is medial view, with anterior to the left: And here's the dorsal view, with anterior to the left.

And here's the dorsal view, with anterior to the left. The teeth are mostly missing, but the back half of the third premolar and the anterior root of the fourth premolar are preserved. Below is dorsal view with the sockets labeled:

The teeth are mostly missing, but the back half of the third premolar and the anterior root of the fourth premolar are preserved. Below is dorsal view with the sockets labeled: This fragment is a good match in both size and morphology for the front half of a coyote, Canis latrans, which have been common in California since the Pleistocene:

This fragment is a good match in both size and morphology for the front half of a coyote, Canis latrans, which have been common in California since the Pleistocene:

Fossil Friday - Foerstephyllum vacuum colony

Western Science Center has a relatively small collection of invertebrate fossils, but we've been working over the last two years to increase our holdings of invertebrate specimens. The specimen shown above is a coral colony from the species Foerstephyllum vacuum. It was collected from the Late Ordovician Drakes Formation in Kentucky, from a unit known as the Otter Creek Coral Bed. There are several coral species found in this unit, with Foerstephyllum being the most prominent.Foerstephyllum is a member of a group of corals known as the Tabulata. The tabulate corals were a highly successful and diverse group that were found worldwide during the Paleozoic Era over a span of more than 200 million years. Like so many other groups, the tabulates went completely extinct at the end of the Permian Period 250 million years ago, when roughly 95% of marine invertebrate species went extinct.

Western Science Center has a relatively small collection of invertebrate fossils, but we've been working over the last two years to increase our holdings of invertebrate specimens. The specimen shown above is a coral colony from the species Foerstephyllum vacuum. It was collected from the Late Ordovician Drakes Formation in Kentucky, from a unit known as the Otter Creek Coral Bed. There are several coral species found in this unit, with Foerstephyllum being the most prominent.Foerstephyllum is a member of a group of corals known as the Tabulata. The tabulate corals were a highly successful and diverse group that were found worldwide during the Paleozoic Era over a span of more than 200 million years. Like so many other groups, the tabulates went completely extinct at the end of the Permian Period 250 million years ago, when roughly 95% of marine invertebrate species went extinct.

Fossil Friday - deer forelimb

Almost all the species alive today were also around during the Ice Age. While they may have been filling different niches in the much more diverse Pleistocene fauna, their remains are very recognizable. WSC has a small collection of fossils from Murrieta that include remains from a number of extant species. Among these are two associated forelimb bones from a deer, the humerus (above) and the radius (below, both in anterior view)

Almost all the species alive today were also around during the Ice Age. While they may have been filling different niches in the much more diverse Pleistocene fauna, their remains are very recognizable. WSC has a small collection of fossils from Murrieta that include remains from a number of extant species. Among these are two associated forelimb bones from a deer, the humerus (above) and the radius (below, both in anterior view) Below are the same two bones in posterior view:

Below are the same two bones in posterior view:

The humerus is missing the proximal 1/3 or so, but is otherwise in good shape. The radius is nearly complete except for a fragment at the distal end. While it's difficult to see in these photos, there is some evidence of gnaw marks from rodents at the distal end of the humerus.Both of these bones are from the left forelimb, and they articulate quite nicely (lateral view, with anterior to the left):

The humerus is missing the proximal 1/3 or so, but is otherwise in good shape. The radius is nearly complete except for a fragment at the distal end. While it's difficult to see in these photos, there is some evidence of gnaw marks from rodents at the distal end of the humerus.Both of these bones are from the left forelimb, and they articulate quite nicely (lateral view, with anterior to the left): These bones are pretty much a perfect match for Odocoileus, the genus that includes the white-tailed deer and the mule deer. They are surprisingly small, however, and are a good bit smaller than the female white-tailed deer I was using as a reference. I'm not sure if this has any significance, since it's difficult to draw generalized conclusions from a single specimen.

These bones are pretty much a perfect match for Odocoileus, the genus that includes the white-tailed deer and the mule deer. They are surprisingly small, however, and are a good bit smaller than the female white-tailed deer I was using as a reference. I'm not sure if this has any significance, since it's difficult to draw generalized conclusions from a single specimen.

Fossil Friday - Proboscidean tusk

While the Diamond Valley Lake Project lasted for several years, it was still essentially a salvage operation. As a result, many of the larger specimens have only been partially prepared. Our staff and volunteers are gradually working through the backlog.For the last few months our volunteer Nathan has been reconstructing a shattered tusk, consisting of a tray with perhaps 300 fragments. His hard work is paying off, as a pretty nice tusk is beginning to take shape. More than half of recovered fragments have been reattached so far. We're not sure yet if this tusk is from a mammoth or a mastodon, although I'm leaning toward the latter. Assuming it is mastodon, it's either from an immature animal or from a female; adult male mastodons have massive tusks that are much larger than this. The tusk is worn at the tip, and there appears to be more than one wear facet. I'd like to say this indicates an older animal, but ivory is relatively soft and wears rapidly, so even a young animal can have substantial wear at the tip of the tusk.The DVL mastodon collection is dominated by adult males, and we don't have a lot of mammoths at any age, so this tusk represents a relatively rare part of the collection no matter what it ultimately turns out to be.

While the Diamond Valley Lake Project lasted for several years, it was still essentially a salvage operation. As a result, many of the larger specimens have only been partially prepared. Our staff and volunteers are gradually working through the backlog.For the last few months our volunteer Nathan has been reconstructing a shattered tusk, consisting of a tray with perhaps 300 fragments. His hard work is paying off, as a pretty nice tusk is beginning to take shape. More than half of recovered fragments have been reattached so far. We're not sure yet if this tusk is from a mammoth or a mastodon, although I'm leaning toward the latter. Assuming it is mastodon, it's either from an immature animal or from a female; adult male mastodons have massive tusks that are much larger than this. The tusk is worn at the tip, and there appears to be more than one wear facet. I'd like to say this indicates an older animal, but ivory is relatively soft and wears rapidly, so even a young animal can have substantial wear at the tip of the tusk.The DVL mastodon collection is dominated by adult males, and we don't have a lot of mammoths at any age, so this tusk represents a relatively rare part of the collection no matter what it ultimately turns out to be.

Fossil Friday - pocket gopher jaw

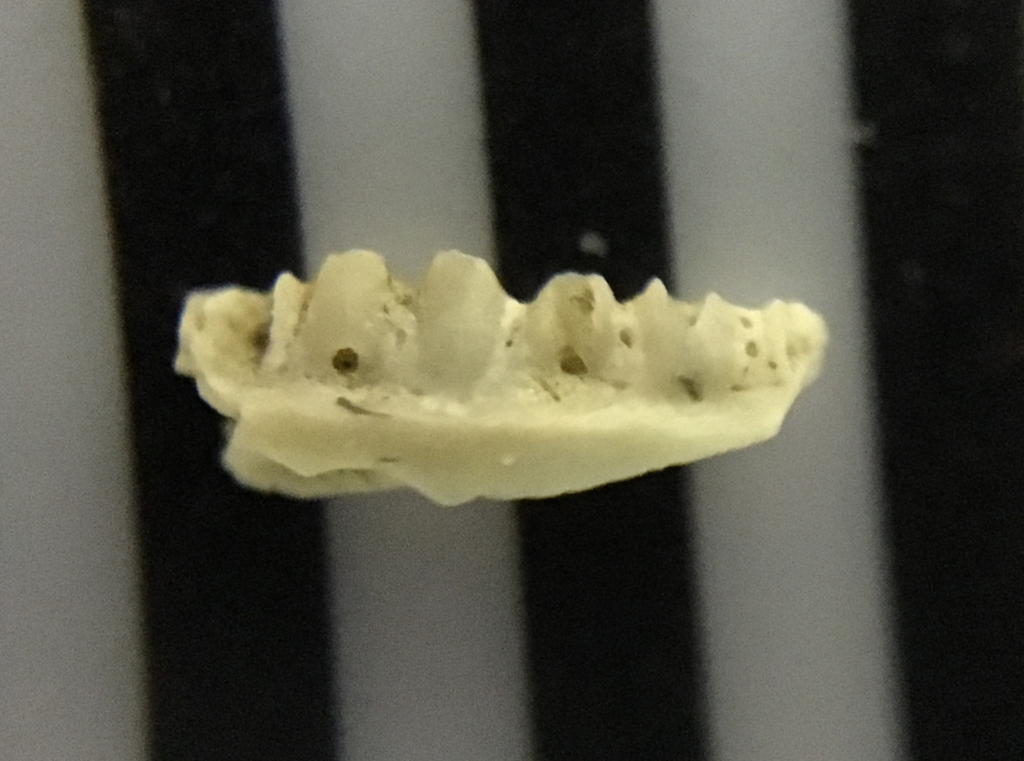

This week's Fossil Friday subject is one of the most common Pleistocene vertebrate fossils in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna; the pocket gopher.Pocket gophers are rodents from the Family Geomyidae, which first evolved in North America during the Oligocene or early Miocene. The family diversified in the late Miocene and Pliocene and is now found throughout the New World.Above is the right dentary (lower jaw) from a western pocket gopher of the genus Thomomys. It's shown in lateral view, with anterior to the right. The anterior end is dominated by the huge ever-growing incisor, which is one of the key features shared among all rodents. In medial view (below), the cheek teeth are more clearly visible:

This week's Fossil Friday subject is one of the most common Pleistocene vertebrate fossils in the Diamond Valley Lake fauna; the pocket gopher.Pocket gophers are rodents from the Family Geomyidae, which first evolved in North America during the Oligocene or early Miocene. The family diversified in the late Miocene and Pliocene and is now found throughout the New World.Above is the right dentary (lower jaw) from a western pocket gopher of the genus Thomomys. It's shown in lateral view, with anterior to the right. The anterior end is dominated by the huge ever-growing incisor, which is one of the key features shared among all rodents. In medial view (below), the cheek teeth are more clearly visible: The back end of the dentary is missing, so the condolences that articulates with the cranium and the coronoid and angular processes where the jaw muscles attach are not preserved. Adult pocket gophers have a total of 5 teeth in each half of the lower jaw, an incisor, the 4th premolar, and 3 molars. In this specimen, the 4th premolar and 3rd molar are missing, which is more obvious in dorsal view:

The back end of the dentary is missing, so the condolences that articulates with the cranium and the coronoid and angular processes where the jaw muscles attach are not preserved. Adult pocket gophers have a total of 5 teeth in each half of the lower jaw, an incisor, the 4th premolar, and 3 molars. In this specimen, the 4th premolar and 3rd molar are missing, which is more obvious in dorsal view: The 4th premolar is a bi-lobed tooth, as is clear from its empty socket. The 1st and 2nd molars are well-preserved and show typical wear for an adult pocket gopher, while the 3rd molar is missing and there's some damage to its socket.Pocket gophers are burrowing animals that make vast tunnel systems where they store their food, but they don't live in large colonies like prairie dogs and other ground squirrels. Thomomys teeth are very common in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits; they are in fact probably the most common vertebrate at DVL, making up nearly 1/3 of all the fossils found there.

The 4th premolar is a bi-lobed tooth, as is clear from its empty socket. The 1st and 2nd molars are well-preserved and show typical wear for an adult pocket gopher, while the 3rd molar is missing and there's some damage to its socket.Pocket gophers are burrowing animals that make vast tunnel systems where they store their food, but they don't live in large colonies like prairie dogs and other ground squirrels. Thomomys teeth are very common in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits; they are in fact probably the most common vertebrate at DVL, making up nearly 1/3 of all the fossils found there.

Fossil Friday - sloth jaw

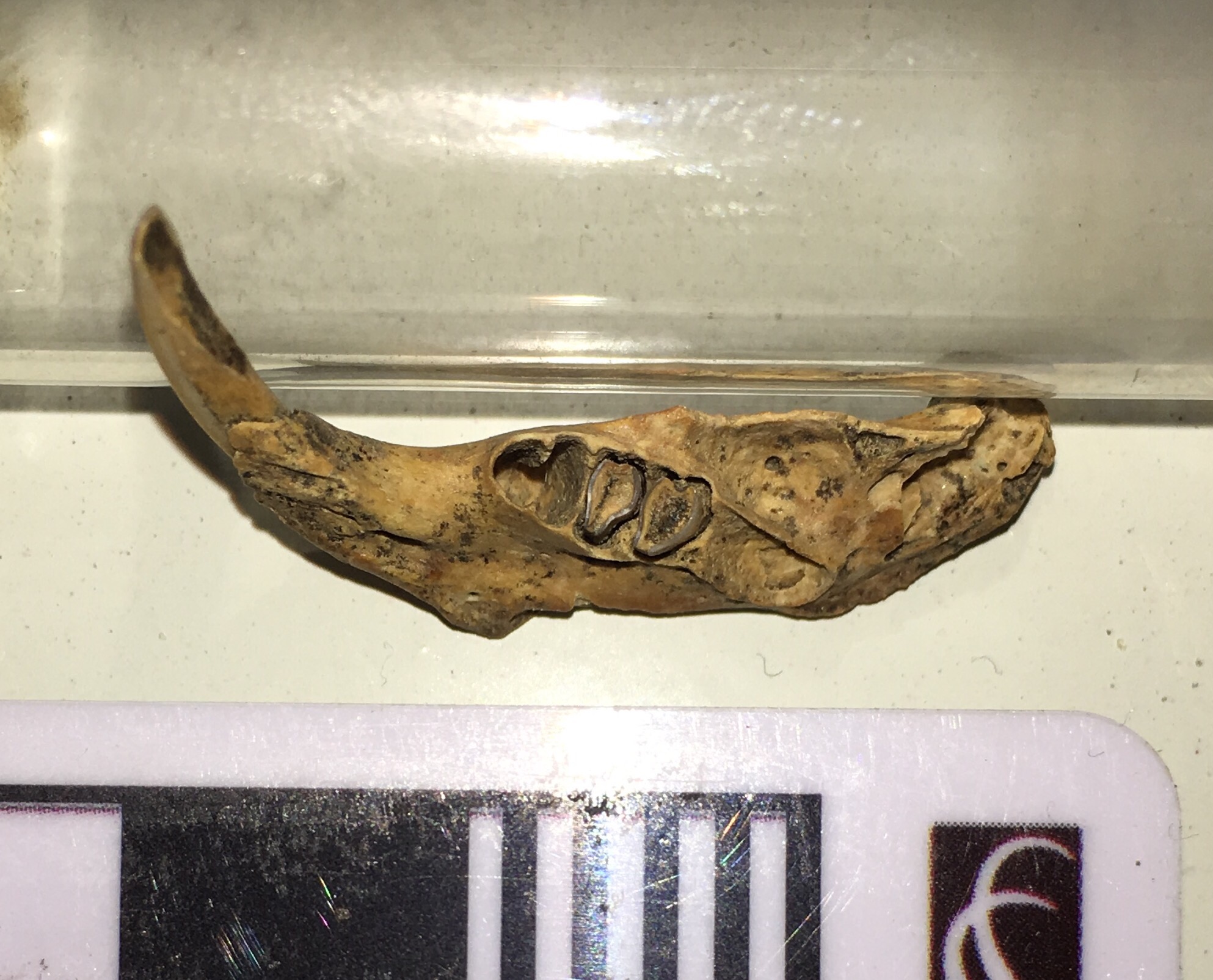

Yesterday was International Sloth Day (with sloth in this case being a noun, not an adjective)! That's a nice day to celebrate at Western Science Center, because Diamond Valley Lake is the only locality in California with three different species of ground sloths. By far the most common sloth at DVL is Harlan's ground sloth, Paramylodon harlani. Shown above is a Paramylodon partial lower jaw. This is the anterior end of the right dentary seen in dorsal view, with anterior to the left. The long straight edge at the lower left is the mandibular symphysis, where the right and left dentaries attach to each other (essentially the chin). The bases of two teeth are visible at the upper right.Here's a lateral view:

Yesterday was International Sloth Day (with sloth in this case being a noun, not an adjective)! That's a nice day to celebrate at Western Science Center, because Diamond Valley Lake is the only locality in California with three different species of ground sloths. By far the most common sloth at DVL is Harlan's ground sloth, Paramylodon harlani. Shown above is a Paramylodon partial lower jaw. This is the anterior end of the right dentary seen in dorsal view, with anterior to the left. The long straight edge at the lower left is the mandibular symphysis, where the right and left dentaries attach to each other (essentially the chin). The bases of two teeth are visible at the upper right.Here's a lateral view: This time the anterior end is on the right. In this view it's clear that the teeth are broken off, and barely protrude above the bone. This is presumably breakage that occurred after the animal died, since the breaks are jagged.This fragment makes an interesting comparison with one of the other DVL sloths, Megalonyx jeffersonii. Paramylodon seems to have a longer, more slender jaw than Megalonyx and lacks the latter's enlarged, chisel-like incisors. That's not entirely surprising; while Paramylodon and Megalonyx are both sloths, they are only distantly related to each other.

This time the anterior end is on the right. In this view it's clear that the teeth are broken off, and barely protrude above the bone. This is presumably breakage that occurred after the animal died, since the breaks are jagged.This fragment makes an interesting comparison with one of the other DVL sloths, Megalonyx jeffersonii. Paramylodon seems to have a longer, more slender jaw than Megalonyx and lacks the latter's enlarged, chisel-like incisors. That's not entirely surprising; while Paramylodon and Megalonyx are both sloths, they are only distantly related to each other.

Fossil Friday - horse jaw

While the majority of Ice Age fossils in Riverside County are from the Diamond Valley Lake excavation, there are a few other productive Pleistocene sites. As with DVL, these have mostly been found during construction projects. The specimen shown above was recovered from The Promenade shopping mall in Temecula.While badly crushed, the specimen is the tip of the lower jaw of a horse. It's shown in dorsal view, with anterior to the left. Mammal lower jaws are made up of two bones, the left and right dentaries. In most species the dentaries are fused together at the chin, in what's technically called the mandibular symphysis; that's what's preserved here.There are actually portions of 8 teeth present in this fragment, although they're poorly preserved. In the marked-up image below, the red areas are indicating the positions of the 6 lower incisors (3 on each side), while the blue arrows are pointing at the bases of the canines (

While the majority of Ice Age fossils in Riverside County are from the Diamond Valley Lake excavation, there are a few other productive Pleistocene sites. As with DVL, these have mostly been found during construction projects. The specimen shown above was recovered from The Promenade shopping mall in Temecula.While badly crushed, the specimen is the tip of the lower jaw of a horse. It's shown in dorsal view, with anterior to the left. Mammal lower jaws are made up of two bones, the left and right dentaries. In most species the dentaries are fused together at the chin, in what's technically called the mandibular symphysis; that's what's preserved here.There are actually portions of 8 teeth present in this fragment, although they're poorly preserved. In the marked-up image below, the red areas are indicating the positions of the 6 lower incisors (3 on each side), while the blue arrows are pointing at the bases of the canines ("wolf teeth" in horse terminology Eric Scott pointed out to me that the "wolf teeth" are actually vestigial 1st premolars, not the canines, so that while these teeth are canines they are not wolf teeth): WSC volunteer Joe has been cleaning this specimen, and is working on other associated fragments. It looks like we probably have additional material from this jaw, which I'll post once it's further prepared.

WSC volunteer Joe has been cleaning this specimen, and is working on other associated fragments. It looks like we probably have additional material from this jaw, which I'll post once it's further prepared.

Fossil Friday - Max's pelvis revisited

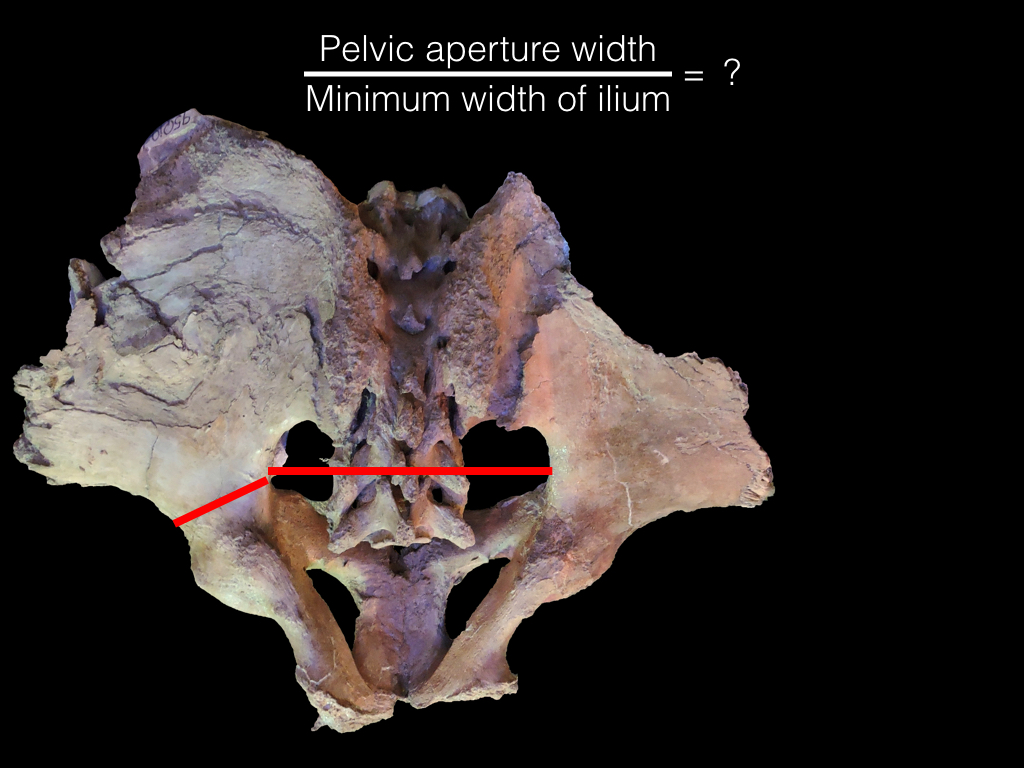

Western Science Center's largest mastodon, Max (@MaxMastodon on Twitter) has been getting a lot of attention over the last year. Besides getting CT scans and figuring prominently in the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" project, this October marks 21 years since Max was discovered. Max is also one of the WSC's major exhibits, and at our recent Science Under the Stars fundraiser we successfully raised funds to add new content to Max's (and other) displays, discussing some of the new things we've learned.Max is not only the largest mastodon known from California, but is also pretty large when compared to mastodons from other parts of the country, so we've long assumed he was male (male mastodons tend to be larger than females). But there are several parts of the skeleton where we can take direct measurements to have greater confidence when identifying Max's sex. One of these areas is the pelvis, which as I've discussed in a prior post is one of the well-preserved parts of Max.Lister (1996) showed that in mammoths males and females consistently differ in the ratio between two pelvic measurements, the pelvic aperture width and the minimum width of the ilial shaft, as shown in the image below:

Western Science Center's largest mastodon, Max (@MaxMastodon on Twitter) has been getting a lot of attention over the last year. Besides getting CT scans and figuring prominently in the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" project, this October marks 21 years since Max was discovered. Max is also one of the WSC's major exhibits, and at our recent Science Under the Stars fundraiser we successfully raised funds to add new content to Max's (and other) displays, discussing some of the new things we've learned.Max is not only the largest mastodon known from California, but is also pretty large when compared to mastodons from other parts of the country, so we've long assumed he was male (male mastodons tend to be larger than females). But there are several parts of the skeleton where we can take direct measurements to have greater confidence when identifying Max's sex. One of these areas is the pelvis, which as I've discussed in a prior post is one of the well-preserved parts of Max.Lister (1996) showed that in mammoths males and females consistently differ in the ratio between two pelvic measurements, the pelvic aperture width and the minimum width of the ilial shaft, as shown in the image below: In female mammoths, this ratio is greater than about 2.6, while it is less than 2.6 in males. Hodgson et al. (2008) and Fisher (2008) found that a similar relationship holds true for mastodons. In Max this ratio is 2.23, which is well on the male end of the spectrum. This is, of course, what we expected to find, but it's still necessary to go through the steps and confirm the results, rather than just assuming we'll get the expected answer.One of the new interactive stations funded by our Science Under the Stars fundraiser is going to feature the methods we used to determine Max's sex, including pelvic dimensions. Below is a draft video explanation of the pelvic measurements we put together for the fundraiser, narrated by WSC volunteer Catalina Lauridsen:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zu4rOYtp9Ng]Tomorrow at WSC we're hosting the first Ice Age Soirée, and over-21 party celebrating 21 years since Max's discovery. Tickets are $40 and include dinner and drinks, as well as admission to the museum.References:Fisher, D. C., 2008. Taphonomy and paleobiology of the Hyde Park mastodon. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:197-289.Hodgson, J. A., Allmon, W. D., Nester, P. L., Sherpa, J. M., and Chimney, J. J., 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:301-367.Lister, A. M., 1996. Sexual dimorphism in the mammoth pelvis: an aid to gender determination. In Shoshani, J. and Tassy, P. eds. The Proboscidea: Evolution and Paleoecology of Elephants and their Relatives. Oxford University Press, pp.254-259.

In female mammoths, this ratio is greater than about 2.6, while it is less than 2.6 in males. Hodgson et al. (2008) and Fisher (2008) found that a similar relationship holds true for mastodons. In Max this ratio is 2.23, which is well on the male end of the spectrum. This is, of course, what we expected to find, but it's still necessary to go through the steps and confirm the results, rather than just assuming we'll get the expected answer.One of the new interactive stations funded by our Science Under the Stars fundraiser is going to feature the methods we used to determine Max's sex, including pelvic dimensions. Below is a draft video explanation of the pelvic measurements we put together for the fundraiser, narrated by WSC volunteer Catalina Lauridsen:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zu4rOYtp9Ng]Tomorrow at WSC we're hosting the first Ice Age Soirée, and over-21 party celebrating 21 years since Max's discovery. Tickets are $40 and include dinner and drinks, as well as admission to the museum.References:Fisher, D. C., 2008. Taphonomy and paleobiology of the Hyde Park mastodon. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:197-289.Hodgson, J. A., Allmon, W. D., Nester, P. L., Sherpa, J. M., and Chimney, J. J., 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:301-367.Lister, A. M., 1996. Sexual dimorphism in the mammoth pelvis: an aid to gender determination. In Shoshani, J. and Tassy, P. eds. The Proboscidea: Evolution and Paleoecology of Elephants and their Relatives. Oxford University Press, pp.254-259.

Fossil Friday - vole tooth

The rodent family Cricetidae is a diverse group that includes animals such as muskrats, pack rats, and hamsters. That diversity is reflected in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits, which contain several different cricetids including one of the most common members of the family, the voles.Voles are small rodents that look vaguely similar to house mice (which are an invasive species in North America and belong to an entirely different family). Below is an example of a meadow vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus, which is found in northern and eastern North America (this one is from Virginia; the small white objects are blowfly eggs):

The rodent family Cricetidae is a diverse group that includes animals such as muskrats, pack rats, and hamsters. That diversity is reflected in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits, which contain several different cricetids including one of the most common members of the family, the voles.Voles are small rodents that look vaguely similar to house mice (which are an invasive species in North America and belong to an entirely different family). Below is an example of a meadow vole, Microtus pennsylvanicus, which is found in northern and eastern North America (this one is from Virginia; the small white objects are blowfly eggs): As with so many mammals, the most commonly preserved fossil remains of voles are their teeth. At the top of the page is a right lower third molar in labial view; the entire tooth is about 3 mm tall. Below is the lingual view of the same tooth:

As with so many mammals, the most commonly preserved fossil remains of voles are their teeth. At the top of the page is a right lower third molar in labial view; the entire tooth is about 3 mm tall. Below is the lingual view of the same tooth: The series of ridges on the side of the tooth are expressed on the occlusal surface as complex loops of enamel. Below is the occlusal view (sorry for the focus, I'm experimenting with a new macro lens for my iPhone):

The series of ridges on the side of the tooth are expressed on the occlusal surface as complex loops of enamel. Below is the occlusal view (sorry for the focus, I'm experimenting with a new macro lens for my iPhone): This pattern of alternating ridges of enamel with areas of dentin serves to keep the tooth sharp as it wears down, and versions of this have evolved independently in almost every group of mammalian herbivores, from rodents to elephants. It's especially common in groups that feed on highly abrasive plants such as grasses, which are in fact the preferred food of voles.The DVL tooth probably comes from Microtus californicus, a species that it still widespread in California except in very arid regions. While probably not as common as the fellow cricetid Neotoma, voles are still a significant component of the DVL fauna.

This pattern of alternating ridges of enamel with areas of dentin serves to keep the tooth sharp as it wears down, and versions of this have evolved independently in almost every group of mammalian herbivores, from rodents to elephants. It's especially common in groups that feed on highly abrasive plants such as grasses, which are in fact the preferred food of voles.The DVL tooth probably comes from Microtus californicus, a species that it still widespread in California except in very arid regions. While probably not as common as the fellow cricetid Neotoma, voles are still a significant component of the DVL fauna.

Fossil Friday - bison jaw fragments

Some of the species in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits are common enough that it's actually possible to get some idea of intraspecies variability, including growth-based (ontogenetic) differences. Bison are not as common at DVL as horses, but there are still enough specimens to look a bit at age profiles. The specimen above is the anterior end of the lower jaw, with portions of both dentaries. This is a dorsal view, with anterior to the left. Below is a lateral view of the left dentary:

Some of the species in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits are common enough that it's actually possible to get some idea of intraspecies variability, including growth-based (ontogenetic) differences. Bison are not as common at DVL as horses, but there are still enough specimens to look a bit at age profiles. The specimen above is the anterior end of the lower jaw, with portions of both dentaries. This is a dorsal view, with anterior to the left. Below is a lateral view of the left dentary: ...and here's right dentary in lateral view:

...and here's right dentary in lateral view: Three teeth are preserved, the right 2nd premolar and the left 2nd and 3rd premolars, none of which have any strong indications of wear. The jaw sections are also quite small compared to other bison in our collection. That raises a question: are these teeth permanent premolars, indicating an animal that was maybe 3 or 4 years old, or are they deciduous premolars, in which case it was probably only a few months old? The small size of the jaw actually makes me suspect the latter. I hope at some point to get x-ray images to see if the permanent premolars are present inside the jaw, although this animal could be so young that they hadn't started to develop yet.

Three teeth are preserved, the right 2nd premolar and the left 2nd and 3rd premolars, none of which have any strong indications of wear. The jaw sections are also quite small compared to other bison in our collection. That raises a question: are these teeth permanent premolars, indicating an animal that was maybe 3 or 4 years old, or are they deciduous premolars, in which case it was probably only a few months old? The small size of the jaw actually makes me suspect the latter. I hope at some point to get x-ray images to see if the permanent premolars are present inside the jaw, although this animal could be so young that they hadn't started to develop yet.

Fossil Friday - Carnivore traces

In any large collection of vertebrate fossils, one of the more common specimen labels will be "unidentified bone fragment". But even an unidentified fragment can provide useful information. The bone shown above, found near the East Dam of DVL, has the following, rather uninspiring label: "Mammalia (larger size), unidentified bone fragment". This might be part of a transverse process or neural spine from a vertebra, and if so is could be from anything from a horse to a juvenile proboscidean. But there are also other possibilities; about the only things we can rule out are animals like rodents and rabbits that don't have any bones at all that are this large.So why is this bone interesting? Note the grooves visible in several places along the margin. Here are some views from different angles:

In any large collection of vertebrate fossils, one of the more common specimen labels will be "unidentified bone fragment". But even an unidentified fragment can provide useful information. The bone shown above, found near the East Dam of DVL, has the following, rather uninspiring label: "Mammalia (larger size), unidentified bone fragment". This might be part of a transverse process or neural spine from a vertebra, and if so is could be from anything from a horse to a juvenile proboscidean. But there are also other possibilities; about the only things we can rule out are animals like rodents and rabbits that don't have any bones at all that are this large.So why is this bone interesting? Note the grooves visible in several places along the margin. Here are some views from different angles:

These nearly-parallel grooves are consistent with gnaw marks from a carnivoran, so this fragment is covered with trace fossils. We can't say with certainty what type of carnivoran made the marks, but they are not particularly large, so it's unlikely we're looking at a huge animal like Arctodus. A medium-sized carnivoran such as a black bear, dire wolf, or coyote is a more likely possibility, or perhaps even a badger; all of these are known from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits.As I've mentioned in previous posts, carnivoran bones are quite rare in the DVL deposits. But we do see evidence of their activity. We haven't yet catalogued all the bite marks that are present on DVL bones, but I suspect we actually have more carnivoran trace fossils than bones in our collection.

These nearly-parallel grooves are consistent with gnaw marks from a carnivoran, so this fragment is covered with trace fossils. We can't say with certainty what type of carnivoran made the marks, but they are not particularly large, so it's unlikely we're looking at a huge animal like Arctodus. A medium-sized carnivoran such as a black bear, dire wolf, or coyote is a more likely possibility, or perhaps even a badger; all of these are known from the Diamond Valley Lake deposits.As I've mentioned in previous posts, carnivoran bones are quite rare in the DVL deposits. But we do see evidence of their activity. We haven't yet catalogued all the bite marks that are present on DVL bones, but I suspect we actually have more carnivoran trace fossils than bones in our collection.

Fossil Friday - seven bone fragments that built a museum

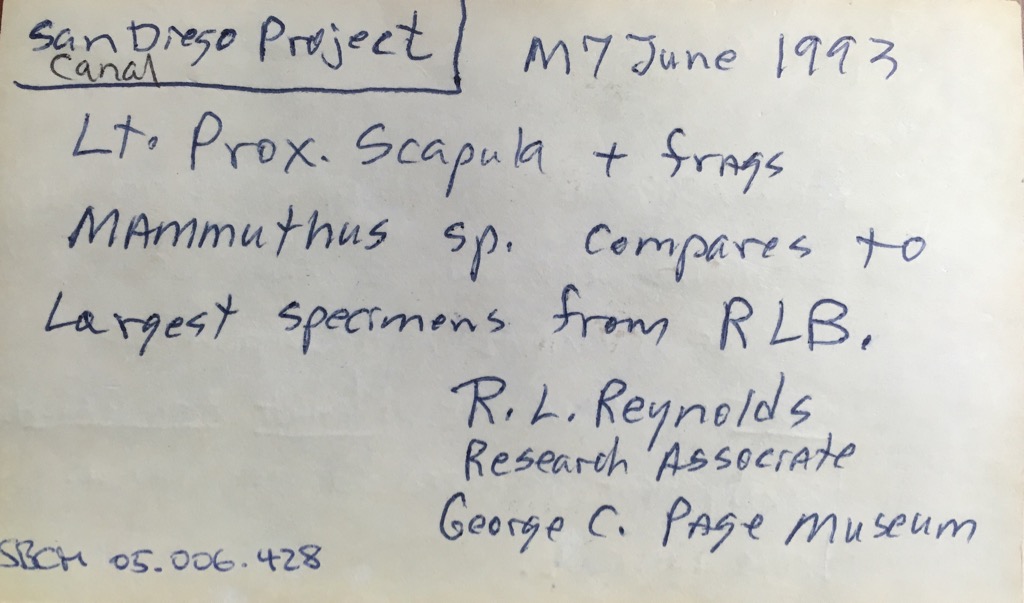

Tomorrow night the Western Science Center is holding the annual Science Under the Stars fundraiser. This year is a particularly special event, because the museum is celebrating its 10th anniversary; we opened to the public for the first time on October 15, 2006.WSC has grown over the last decade into a major regional museum and has brought in collections from a variety of locations, but the original reason we were founded was to house the collections recovered during the construction of Diamond Valley Lake and its related projects, such as the San Diego Canal and Domenigoni Parkway. These specimens still make up the majority of our collections.The seven bone fragments shown above we discovered by archaeologist Melinda Horne on 7 June 1993 along the path of the San Diego Canal. They don't look like much, but one thing is immediately obvious; they're pretty big fragments. The only animals found in California today (outside of zoos) that are even remotely close to being large enough to produce bones like these are horses and cows , and these fragments seem too large even for those. The largest fragment is a bit better preserved than the others; here's a different view:

Tomorrow night the Western Science Center is holding the annual Science Under the Stars fundraiser. This year is a particularly special event, because the museum is celebrating its 10th anniversary; we opened to the public for the first time on October 15, 2006.WSC has grown over the last decade into a major regional museum and has brought in collections from a variety of locations, but the original reason we were founded was to house the collections recovered during the construction of Diamond Valley Lake and its related projects, such as the San Diego Canal and Domenigoni Parkway. These specimens still make up the majority of our collections.The seven bone fragments shown above we discovered by archaeologist Melinda Horne on 7 June 1993 along the path of the San Diego Canal. They don't look like much, but one thing is immediately obvious; they're pretty big fragments. The only animals found in California today (outside of zoos) that are even remotely close to being large enough to produce bones like these are horses and cows , and these fragments seem too large even for those. The largest fragment is a bit better preserved than the others; here's a different view: The large, flat surface (where the number is painted) is an articular surface, where this bone articulated with another bone. Even though it's incomplete, there's enough preserved to identify this as the joint surface on the shoulder blade (technically, the glenoid fossa of the scapula). And that gives us another clue; this bone is far too large to be the glenoid fossa from a horse or a cow. The only common things in California this big are extinct Pleistocene elephants. This bone established the presence of Ice Age deposits in the area.This was noted by R. L. Reynolds from the George C. Page Museum, who tentatively identified the specimen as a mammoth, as written on an index card stored with the specimen:

The large, flat surface (where the number is painted) is an articular surface, where this bone articulated with another bone. Even though it's incomplete, there's enough preserved to identify this as the joint surface on the shoulder blade (technically, the glenoid fossa of the scapula). And that gives us another clue; this bone is far too large to be the glenoid fossa from a horse or a cow. The only common things in California this big are extinct Pleistocene elephants. This bone established the presence of Ice Age deposits in the area.This was noted by R. L. Reynolds from the George C. Page Museum, who tentatively identified the specimen as a mammoth, as written on an index card stored with the specimen: Several years later, Eric Scott (who is now at the Cooper Center, and is one of my collaborators on the Mastodons of Unusual Size project), examined the specimen and considered it more likely to be from a mastodon than a mammoth (his notes were written on the back of the same index card):

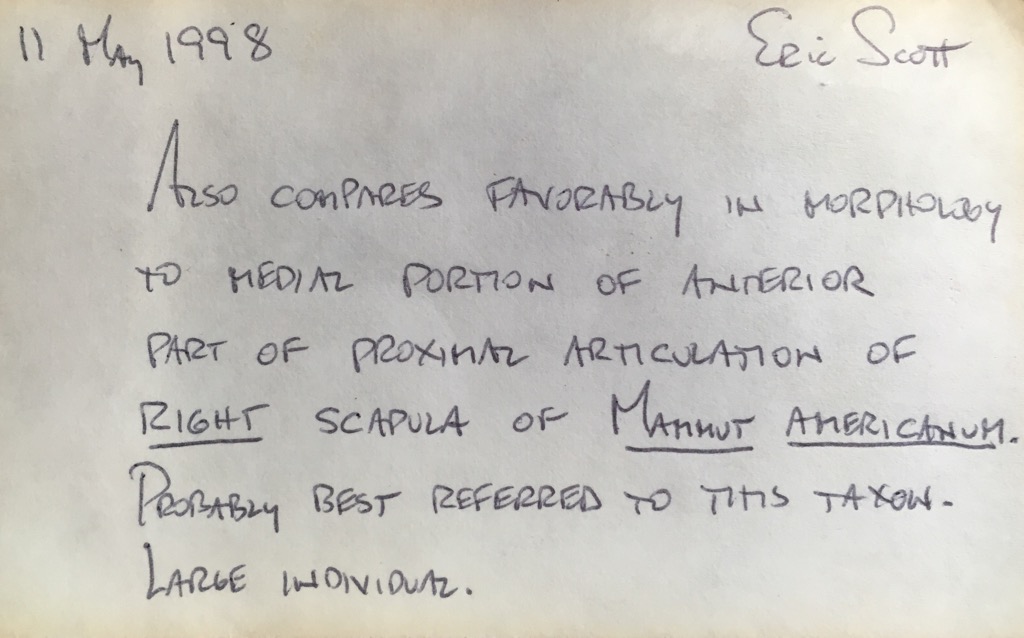

Several years later, Eric Scott (who is now at the Cooper Center, and is one of my collaborators on the Mastodons of Unusual Size project), examined the specimen and considered it more likely to be from a mastodon than a mammoth (his notes were written on the back of the same index card): To give an idea of what Eric was seeing, here's a glenoid fossa view of the Watkins Glen mastodon from New York (this image is modified from Hodgson et al., 2008)...

To give an idea of what Eric was seeing, here's a glenoid fossa view of the Watkins Glen mastodon from New York (this image is modified from Hodgson et al., 2008)... ...and here's the same image with the California fragment scaled to the same size and superimposed:

...and here's the same image with the California fragment scaled to the same size and superimposed: That's a pretty good match, and I agree with Eric that this is probably from a mastodon, the first from the project.These seven fragments put paleontologists and engineers on alert that there could be additional Pleistocene fossils uncovered during the construction of the reservoir. As the project progressed, more specimens were uncovered, and 2 years after the initial find Max was discovered. Over the next decade more than 100,000 fossils were recovered in the area, a collection so large that a new museum was built to house it, and tomorrow night we'll celebrate that museum's tenth anniversary.A fossil doesn't have to look impressive to be important. Reference:Hodgson, J. A., W. D. Allmon, P. L. Nester, J. M. Sherpa, and J. J. Chimney, 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and P. L. Nester (eds.), 2008. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Palaeontographica Americana 61:301-367. Available for purchase.

That's a pretty good match, and I agree with Eric that this is probably from a mastodon, the first from the project.These seven fragments put paleontologists and engineers on alert that there could be additional Pleistocene fossils uncovered during the construction of the reservoir. As the project progressed, more specimens were uncovered, and 2 years after the initial find Max was discovered. Over the next decade more than 100,000 fossils were recovered in the area, a collection so large that a new museum was built to house it, and tomorrow night we'll celebrate that museum's tenth anniversary.A fossil doesn't have to look impressive to be important. Reference:Hodgson, J. A., W. D. Allmon, P. L. Nester, J. M. Sherpa, and J. J. Chimney, 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and P. L. Nester (eds.), 2008. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Palaeontographica Americana 61:301-367. Available for purchase.

Fossil Friday - Xena the Mammoth's femur

Mastodons were the most common proboscideans in Diamond Valley, but they weren't the only ones there. Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi) were also present, although in much smaller numbers. The most complete Columbian mammoth from DVL is Xena, whose partial skeleton is on permanent exhibit at the Western Science Center.Xena's remains include the left femur (thigh bone), shown above in anterior view with the proximal end on the left. As is typical of Columbian mammoths, the femur is relatively long and slender when compared to mastodons. While adult mammoths and mastodons were probably pretty comparable in terms of weight, mammoths were quite a bit taller because of their long legs, which were proportioned more like those of modern elephants than the relatively short, thick legs of mastodons. Xena was not particularly tall for a Columbian mammoth, but was at least as tall as Max, the biggest mastodon known from California.

Mastodons were the most common proboscideans in Diamond Valley, but they weren't the only ones there. Columbian mammoths (Mammuthus columbi) were also present, although in much smaller numbers. The most complete Columbian mammoth from DVL is Xena, whose partial skeleton is on permanent exhibit at the Western Science Center.Xena's remains include the left femur (thigh bone), shown above in anterior view with the proximal end on the left. As is typical of Columbian mammoths, the femur is relatively long and slender when compared to mastodons. While adult mammoths and mastodons were probably pretty comparable in terms of weight, mammoths were quite a bit taller because of their long legs, which were proportioned more like those of modern elephants than the relatively short, thick legs of mastodons. Xena was not particularly tall for a Columbian mammoth, but was at least as tall as Max, the biggest mastodon known from California. While Xena's femur is well preserved, it is missing both the proximal and distal ends.These were lost because they had not yet fused to the rest of the femur, indicating that Xena was still growing (even at 3 m tall!). This is also borne out by her teeth; Xena's 1st molars were in wear, but the 2nd molars were completely unerupted, suggesting that she was probably only about 18-20 years old.

While Xena's femur is well preserved, it is missing both the proximal and distal ends.These were lost because they had not yet fused to the rest of the femur, indicating that Xena was still growing (even at 3 m tall!). This is also borne out by her teeth; Xena's 1st molars were in wear, but the 2nd molars were completely unerupted, suggesting that she was probably only about 18-20 years old.

Fossil Friday - dire wolf tooth

Today is National Dog Day, and while the day is primarily honoring domestic dogs (Canis familiaris, or Canis lupus familiars), it seems fitting to also recognize their wild ancestors and cousins.The Diamond Valley Lake deposits only produced a handful of carnivores bones, but several canids are included among their numbers. There are a few individual bones and teeth from dire wolves (Canis dirus), the same species that is so spectacularly common at Rancho La Brea, 80 miles to the west.The partial tooth shown above is currently on exhibit at the Western Science Center, so rather than open the exhibit case (a 3-hour exercise) I instead photographed it through the glass. This rather large tooth is a carnassial, shearing teeth developed to varying degrees among all the carnivorans. The upper carnassials are modified 4th premolars, while the lower ones are the first molars. These teeth occlude like a pair of scissors, and are effective at chopping up flesh from prey animals.While it's difficult to do a detailed examination through glass, I'm pretty sure this is the upper right 4th premolar, seen in lingual view, with the anterior edge broken off and the point worn away. Compare it to a modern coyote upper P4 in the same orientation, below:

Today is National Dog Day, and while the day is primarily honoring domestic dogs (Canis familiaris, or Canis lupus familiars), it seems fitting to also recognize their wild ancestors and cousins.The Diamond Valley Lake deposits only produced a handful of carnivores bones, but several canids are included among their numbers. There are a few individual bones and teeth from dire wolves (Canis dirus), the same species that is so spectacularly common at Rancho La Brea, 80 miles to the west.The partial tooth shown above is currently on exhibit at the Western Science Center, so rather than open the exhibit case (a 3-hour exercise) I instead photographed it through the glass. This rather large tooth is a carnassial, shearing teeth developed to varying degrees among all the carnivorans. The upper carnassials are modified 4th premolars, while the lower ones are the first molars. These teeth occlude like a pair of scissors, and are effective at chopping up flesh from prey animals.While it's difficult to do a detailed examination through glass, I'm pretty sure this is the upper right 4th premolar, seen in lingual view, with the anterior edge broken off and the point worn away. Compare it to a modern coyote upper P4 in the same orientation, below: So if you're celebrating National Dog Day, maybe take some time to visit your local natural history museum and remember our canine friends' extinct relatives!

So if you're celebrating National Dog Day, maybe take some time to visit your local natural history museum and remember our canine friends' extinct relatives!

For those in Southern California, the Western Science Center will be attending NerdCon at the California Center for the Arts in Escondido this weekend. There will be opportunities to take selfies with Max, and we'll have numerous replicas on display (including a dire wolf skull). You'll also be able to purchase detailed replicas of some of our fossils, so if you're attending NerdCon make sure to stop by our booth!

Fossil Friday - Pupilla muscorum

To human eyes, the most noticeable parts of every ecosystem are the big, charismatic organisms; there's a reason the blog is called "Valley of the Mastodon". But in terms of numbers of individuals and, usually, total biomass, small organisms actually dominate ecosystems. That's often reflected in the fossil record as well.Pupilla muscorum is a tiny, air-breathing terrestrial snail (snails are one of a fairly small number of organisms to successfully invade the land). The black bars under the shell shown above are each 1 mm wide, so the entire shell is less than 4 mm long. Shells from this species are quite common in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits; below are the specimens recovered from a single DVL locality:

To human eyes, the most noticeable parts of every ecosystem are the big, charismatic organisms; there's a reason the blog is called "Valley of the Mastodon". But in terms of numbers of individuals and, usually, total biomass, small organisms actually dominate ecosystems. That's often reflected in the fossil record as well.Pupilla muscorum is a tiny, air-breathing terrestrial snail (snails are one of a fairly small number of organisms to successfully invade the land). The black bars under the shell shown above are each 1 mm wide, so the entire shell is less than 4 mm long. Shells from this species are quite common in the Diamond Valley Lake deposits; below are the specimens recovered from a single DVL locality: Today, P. muscorum is found across the northern hemisphere, but especially in Europe. It appears that many of the modern North American occurrences are actually descended from recent invasive European populations, and there is some debate as to whether or not native North American specimens such as the ones from DVL are actually the same species. The shells are extremely similar, so genetic testing of modern populations will probably be necessary to answer this question.

Today, P. muscorum is found across the northern hemisphere, but especially in Europe. It appears that many of the modern North American occurrences are actually descended from recent invasive European populations, and there is some debate as to whether or not native North American specimens such as the ones from DVL are actually the same species. The shells are extremely similar, so genetic testing of modern populations will probably be necessary to answer this question.